A group of scientists from several nations believes it may have discovered one of the factors that differentiate between a normal, conscious brain, and one belonging to a person in a vegetative state.

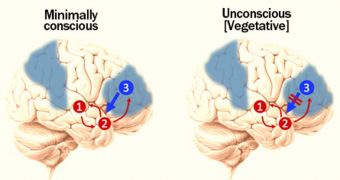

Investigators found a number of cortical loops, that they say are broken in people who are not conscious. This may help explain why they are unresponsive to stimuli, but can still carry out a host of other functions that do not require conscious control.

The signaling malfunction the team encountered developed when communications between the frontal cortex, the area of the brain other studies demonstrated to be involved in decision-making, and other areas of the brain were disrupted.

The international team of researchers provides additional insight into its discovery in a paper published in the May 12 issue of the top journal Science. One of the reasons why such studies are very important is because they may soon help doctors diagnose a vegetative brain.

Placing this diagnostic is a tricky job today, due to the multitude of factors involved in this, and the hazy, still-unknown interplay that develops between them. The new study was coordinated by experts with the Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania.

Institute director John Whyte says that patients who are in a vegetative state cannot act in any purposeful way under observable circumstances. But he stresses that there is a big difference between these patients and those who are minimally conscious.

Patients in the latter group are capable of interacting with people by either moving a finger, or doing some other gesture, in direct response to the requests or questions that are asked of them. At this time, doctors need weeks to discern between the two, and the percentage of misdiagnoses is very high.

In the new study, investigators from the University of Liège in Belgium, led by expert Mélanie Boly, subjected healthy individuals, minimally conscious patients and people in a vegetative state to pulsing blips of sound.

When the intensity or pitch of the sound changed, the brains of healthy volunteers and minimally conscious patients exhibited a spike in neural activity in response, but the answer was not observed in participants in a vegetative state.

In the end, the team determined that an important, neural communications loop was destroyed in the latter group. In healthy people the auditory cortex sends data to the frontal cortex whenever it hears something unusual.

The frontal cortex then sends the data back, and this pathway enters a loop of sorts. This does not happen in vegetative individuals, the team says. “The bottleneck, if you will, is the top-down connection,” Boly explains, quoted by Science News.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //