A paper published in yesterday's issue of the journal Nature details the use of skin cells to engineer neural clumps that would be best described as mini-brains.

In order to create these miniature brains, the researchers first converted the skin cells into stem cells.

The latter were then placed on a synthetic gel that mimicked natural connective tissues found not just in the brain, but also in other bodily parts.

The stem cells did not take long to set up camp in this environment, sources say. When the scientists exposed them to oxygen and nutrients, they started to grow and eventually formed clumps of brain tissue.

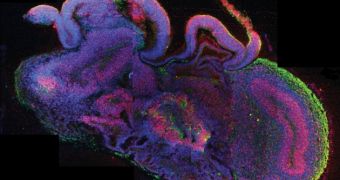

By the looks of it, the tissue balls created during these experiments measure no more than 3-4 millimeters (0.11 - 0.15 inches) in diameter.

Researchers say that, as far as they can tell, they aren't all that different to the brains of fetuses in the ninth week of development.

The scientists were not able to pin down any recognizable physiological structure, meaning that the mini-brains' makeup was fairly random.

Besides, the balls of tissue did not have any blood vessels, which is probably the reason why they did not grow any bigger than the average pea.

However, they claim that the balls of tissue do show signs of having discrete brain regions whose behavior suggests that they can interact with one another.

The researchers who worked on this project explain that these pea-sized chunks of tissue are intended to help scientists gain a better understanding of human neurological diseases.

Thus, when comparing mini-brains grown from skin cells collected from a microcephaly patient to mini-brains made from skin cells taken from healthy individuals, the researchers found that the former did not grow as big.

This might help shed new light on the underlying causes of said medical condition.

“We turned patient derived cells into primitive cells called iPS cells and then used those to generate the cerebral organoids and compare them to ones from healthy patients.”

“Ultimately, we would like to use them to study more common disorders like schizophrenia or autism as it has been shown the underlying defects occur during the development of the brain,” Professor Juergen Knoblich said, as cited by Daily Mail.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //