Morphine, heroine and other opioid drugs are the best known painkillers, but they come with a high risk: in many patients they provoke addiction, the body requiring gradually increasing amounts to ease pain. A new study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience and carried on in rats revealed that inhibiting morphine's action on glia, auxiliary cells of the nervous system, the addiction risk is reduced while increasing the drug's action against pain.

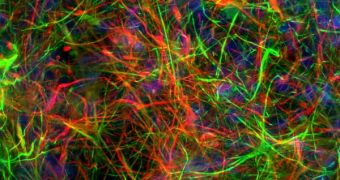

Researchers made in the last 10 years revealed that glial cells can increase nerve pain, like in the case of sciatica, by turning on the neurons that send pain signals. Morphine interferes with nerve synapses, but it also turns on glial cells and this could provoke the drug's side effects, like drowsiness, tolerance, increased pain and addiction.

To see the connection between glia and morphine addiction, the scientists checked if by stopping morphine's effects on glial cells would impede rats from craving the drug. Two teams made up of neuroscientists Linda Watkins and Mark Hutchinson of the University of Colorado, Boulder, worked with AV411, a drug stopping morphine's action only on glia, neurons being not affected by this chemical.

AV411 boosted morphine's pain killing effect on rats that displayed less pain sensitivity than rats given morphine alone. Over time, morphine had longer-lasting pain-relieving effects in the rats receiving also AV411.

The morphine-consuming animals learned that they would receive a drug in one area and not in another. Morphine addicted animals tended to turn back to the drug area ceaselessly, but rodents receiving AV411-plus-morphine did turn back to the area much less than the morphine-only group.

These findings "play a previously unsuspected role in pathological pain. The research helps pave the way toward developing new, potent, nonaddictive medications," said Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse,

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //