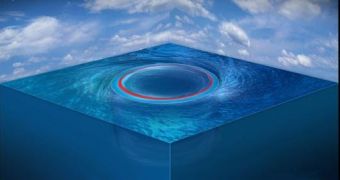

Large eddies, i.e. whirlpools, that form in our planet's oceans are similar to black holes found in outer space, researchers with ETH Zurich and the University of Miami argue in a paper published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics.

More precisely, these researchers maintain that, according to their investigations, eddies are the mathematical equivalent of black holes.

Thus, they attract whatever objects happen to come too close to them, and none of them, regardless of how big or how small they might be, stands any chance to escape once they get caught up on the vortex.

Interestingly enough, water molecules that get caught up in one such whirlpool also find that they are unable to leave the swirl.

“These eddies are so tightly shielded by circular water paths that nothing caught up in them escapes,” ETH Zurich explains. Furthermore, “Fluid particles move around in closed loops. And as in a black hole, nothing can escape from the inside of these loops, not even water.”

From this standpoint, they are best described as coherent water islands, researchers say.

What fascinates scientists is the fact that they somehow manage to form and keep their integrity despite the fact that their surrounding environment is highly complex, and dominated by numerous oceanic currents.

The same source tells us that some of these eddies can grow to measure an impressive 150 kilometers (93.2 miles) in diameter. They move across the ocean and, by doing so, they encourage water mixing.

“Because black-hole-type ocean eddies are stable, they function in the same way as a transportation vehicle - not only for micro-organisms such as plankton or foreign bodies like plastic waste or oil, but also for water with a heat and salt content that can differ from the surrounding water,” ETH Zurich tells us.

Satellite observations have shown that, over the past few years, the number of eddies that form and move across the Southern Ocean has been steadily increasing. Specialists theorize that their presence in these waters ups the amount of warm and salty water that moves northwards.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //