A paper published in yesterday's issue of the journal PLOS ONE details the use of digital imaging and 3D reconstruction to diagnose a 100,000-year-old case of brain damage considered one of the earliest injuries of this kind thus far documented in modern humans.

Scientists behind this research project explain that the skull they reconstructed and whose makeup they analyzed as part of this investigation was left behind by a child who lived during the Paleolithic Era.

As detailed in the journal PLOS ONE, the skull was unearthed at an archaeological site in lower Galilee, Israel, not too long ago. Evidence indicates that it belonged to a child about 12-13 years old, Science Daily tells us.

Shortly after the skull was discovered and dug out, researchers started questioning the circumstances of the child's death. Thus, they noticed that the skull displayed several lesions, and began wondering how this had come to happen.

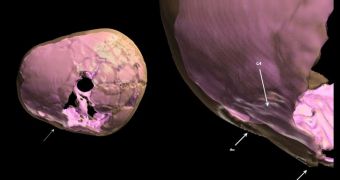

Hoping to gain a better understanding of the child's life and possibly tragic death, specialists resorted to digital imaging and 3D reconstruction to better examine the skull. These technologies made it possible for them to pin down signs of violent head trauma.

Interestingly enough, evidence indicates that this trauma occurred sometime before the child passed away. Scientists still cannot say whether the injury was accidental or purposely inflicted, but what they do know is that the trauma caused severe brain damage.

In fact, it is believed that, between the time the child sustained these injuries and the time death occurred, this ancestor of ours experienced personality changes, had trouble communicating with others, and even found it difficult to control body movements.

Oddly enough, it looks like the child was well treated during his lifetime, and even received special attention after death. Thus, the body was laid to rest together with two deer antlers, suggesting that whoever buried him went through the trouble of staging a ceremony.

The fact that this child was well looked after while he was still alive and that his remains were not simply disposed of but instead buried during a proper ceremony indicates that early humans were no strangers to compassion and did not discriminate against the disabled.

“Digital imaging and 3D reconstruction evidenced the oldest traumatic brain injury in a Paleolithic child. Post-traumatic neuropsychological disorders could have impaired social life of this individual who was buried, when teenager, with a special ritual raising the question of compassion in Prehistory,” says researcher Hélène Coqueugniot.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //