Experts with the European Space Agency (ESA) say that satellites in Earth's orbit are beginning to notice signs indicating that the permafrost at high northern latitudes is thawing and melting. The fact that this is visible from space is very bad news.

Permafrosts, as the name suggests, are permanently frozen soils, which contain vast amounts of organic material that has not yet fully degenerated. When they melt, these soils release vast amounts of methane (CH4), an extremely potent greenhouse gas (GHG).

CH4 is about 300 times more effective at supporting the greenhouse effect leading to global warming than carbon dioxide (CO2) is. In addition, it is poisonous for humans, and can kill very quickly. Instances when animals roaming the permafrost are killed by gas emissions are, unfortunately, not rare.

The situation is made even worse by the fact that the poles are more likely to suffer from the effects of global warming than Earth's equator, for example. All permafrosts are located at high latitudes, near both poles. Climate scientists say that we must avoid the release of CH4 from these sources at all costs.

You are most likely to come across permafrost soils in Alaska, Siberia and Northern Scandinavia, or at very high altitudes, as those found in the Andes, Himalayas and the Alps. It is estimated that about 50 percent of all organic carbon on the planet is trapped in these soils.

This is a massive amount, nearly twice as high as that currently found in the atmosphere. “The effects of climate change are most severe and rapid in the Arctic, causing the permafrost to thaw,” an ESA press release explains.

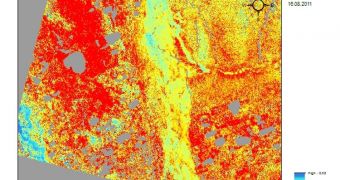

“When it does, it releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere […]. Although permafrost cannot be directly measured from space, factors such as surface temperature, land cover and snow parameters, soil moisture and terrain changes can be captured by satellites,” the document adds.

The agency used a number of its satellites to investigate northern permafrosts. Its flagship asset, Envisat, was used to collect the highest amount of data. The upcoming Sentinel satellite series, part of the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) program, will continue these studies.

“Combining field measurements with remote sensing and climate models can advance our understanding of the complex processes in the permafrost region and improve projections of the future climate,” Dr Hans-Wolfgang Hubberten explains.

The expert is the head of the Alfred Wegner Institute Research Unit, in Germany, and president of the International Permafrost Association.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //