After the European Space Agency (ESA) launched its Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) satellite, experts soon observed that the spacecraft was unable to transmit properly due to interferences. Now that those have been removed, SMOS products are more detailed than ever.

Pirate radio signals were abusively covering up a part of the spectrum in which the spacecraft was relaying its salinity data back to Earth. ESA mission controllers could therefore see only a portion of the data the observatory was collecting.

Soon after the cause of the damage was identified, ESA started a massive international effort to root out these harmful signals that were jamming its advanced satellite. The pirate signals were transmitting in a a reserved wavelength band, illegally.

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) has established that the 1400–1427 MHz band is allocated exclusively to space research, radio astronomy, and Earth Exploration Satellite Services.

This means that no one else is allowed to transmit their signal in this band. But ESA soon realized that the official restriction did not bother operators. The pirates were hampering with important scientific data, covering Earth's water cycle.

SMOS is also involved in analyzing the microwave radiation that the Earth is emitting. Its passive radiometer – which operates in the L-band, between 1400 and 1427 MHz – could not collect and transmit proper readings without substantial interferences.

“SMOS is well on the way to meeting its research objectives over areas free of this radio-frequency interference. However, the mission has clearly not been reaching its full potential because significant amounts of data have had to be discarded,” an ESA press release says.

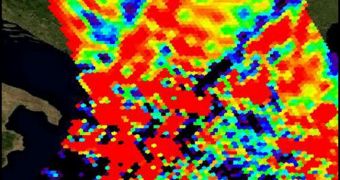

“The areas worst affected are in southern Europe, southern and eastern Asia and the Middle East,” the statement goes on to say. ESA methodically identified the sources of interference, and then coordinated with local authorities in the troublesome regions to suppress the signals.

ESA researchers “have revealed that most of the problems stem from unauthorized transmitters in the protected band such as TV and other radio links and wireless-camera monitoring systems,” scientists with the space agency explain.

“Emissions from air surveillance radar and other radiolocation systems are also common sources of interference,” they conclude.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //