At this point, American soldiers fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq are under constant threat from improvised explosive devices (IED) that rebels plant on commonly-traveled roads. A new detection method produced in the United States proposes the use of lasers to identify the locations of buried IED.

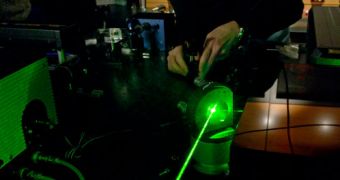

Michigan State University (MSU) researchers say that the laser they developed has the same output as a common presentation pointer. They add that the advanced technology behind this specific device has the ability to scan large areas for hidden threats.

If their efforts to create such an instrument succeed, then the team would have single-handedly been responsible for reducing the appalling rate at which coalition soldiers die from IDE explosions. About 60 percent of all casualties registered thus far were accounted for by road-side bombs.

Details of how the innovative laser system functions are published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Applied Physics Letters. The research team was led by MSU chemistry professor Marcos Dantus, who is also the founder of the company BioPhotonic Solutions.

Detecting IDE in the desert, he explains, is a lot more difficult than in other environments because multiple contaminating chemicals in the air mask the faint signature of molecules given off by explosive substances.

“Having molecular structure sensitivity is critical for identifying explosives and avoiding unnecessary evacuation of buildings and closing roads due to false alarms,” the investigator says, adding that most IDE are planted in densely-populated area, for maximum effect.

With the new laser, it is possible to distinguish the faint chemical signatures of such compounds even in urban areas, where similar chemicals may be emitted in the air from other, harmless sources. Making this distinction is vital to the efficiency of the new system.

“The laser and the method we’ve developed were originally intended for microscopes, but we were able to adapt and broaden its use to demonstrate its effectiveness for standoff detection of explosives,” Dantus explains.

He adds that the MSU team now needs additional funds to translate their laser into practical devices, which can then be deployed on theaters of operations, as needed. Future improvements could increase the range at which the system operates with a high chance of success.

The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) contributed a part of the funds needed for this study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //