One of the most important properties of the human brain is called plasticity. It refers to the ability of the cortex to adapt to new stimuli all the time. While people are young, this ability is at work almost all of the time, breaking apart and creating new synapses and neural pathways, in an attempt to keep up with all the new experiences each individual lives. Neuroscientists say that this flexibility is usually lost after the years of one's youth, but a new study, conducted on unsuspecting mice, reveals that there may be a way of restoring these brain functions even in seniors, Technology Review reports.

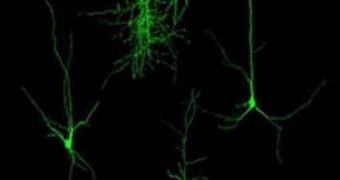

In a paper published in the February 26 issue of the respected journal Science, experts show that transplanting fetal neurons into the brains of young mice restores this ability, and makes the brain exhibit plasticity as before. This line of study could eventually provide scientists with methods of doing the same in older humans, who may experience the ill effects of losing the ability to adapt to external stimuli and experiences. In addition, specialists say, it may be that this approach could provide a new angle of treatment for a wide range of mental disorders, and brain injuries, by simply returning the brain to a younger and more flexible state.

This approach resembles the one microbiologists and geneticists employ to obtain induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). These cell lines are obtained from adult, differentiated cells, which are forced to revert back to their undifferentiated state. They can then be coerced to develop into other type of cells than the ones they were derived from. “[The findings] reveal there must be a factor that can induce plasticity in the brain. We hope that future studies will reveal what it is that allows the cells to induce this new period of plasticity,” University of California in San Francisco (UCSF) neuroscientist Michael Stryker says.

In the mouse study, it was revealed that the transplanted neurons seemed to force a second period of malleability in the brain. Usually, this takes place when the rodent is 25 to 30 days old, but the transplanted nerve cells triggered the changes when they reached this age, and not when the animal hosting them did. At this point, investigators are looking into the exact mechanisms that promote these events, in hopes of drawing conclusions that could also be applied to humans.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //