Determining the distance various objects are from Earth is a critical component of astronomical studies, and one of the key traits of space studies. However, establishing these distances is not easy, and now experts are working on developing a new method that will aid them in this regard.

Astronomers are working on constructing what could best be described as an orbital “light bulb,” a light source that could be used in reference studies meant to determine some very important aspects of our atmosphere.

The fact that air interacts with light emitted by distant objects is no longer a mystery to anyone, but the exact extent to which the atmosphere absorbed wavelengths is not yet know with absolute certainty.

Putting a light source in low-Earth orbit (LEO) would basically allows researchers to have constant access to such data, and then derive more precise measurements from analyzing other bodies. The orbital light would serve as a reference point to see how much light the atmosphere absorbs.

Astronomers reveal that all telescopes have individual light bulbs that allow their operators to conduct calibration procedures. The NASA Hubble Space Telescope, for example, has tungsten bulbs on board.

Given that modern observatories have reached the limits of what can be seen in the Universe, peering as far back in space as 500 million years after the Big Bang, it stands to reason that new data will only be obtained by refining existing technologies, and adapting them for more thorough observations.

One of the most important studies being conducted today is analyzing the expansion of the Universe. This is done by observing light emitted by distant type 1a supernovae located very far away.

Measurements of how much these objects move away from each other are the foundation of the cosmic expansion theory. But understanding expansion in detail requires more precise observations, which themselves require better calibration.

“The addition of man-made calibrated light sources in space to the arsenal of techniques for photometric calibration will provide a powerful new tool for increasing precision in astrophysics,” argues expert Justin Albert.

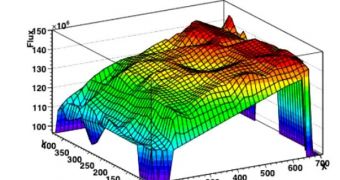

The expert holds an appointment with the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Victoria, in Canada, Technology Review reports. He explains that a calibrated light source placed in orbit would enable scientists to determine how much light the atmosphere absorbs at all frequencies.

He explains that the effort to do so would be minimal, arguing that a single, 25-watt light bulb placed in a circular orbit some 700 kilometers above the surface of the planet would be just as bright to the telescopes of today as a magnitude-12.5 star.

The expert details his idea in a paper published in the open-access journal arXiv.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //