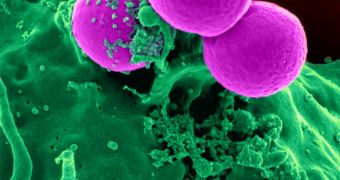

Scientists with the Columbia University Medical Center in New York, led by microbiologist Anne-Catrin Uhlemann, determined in a new study that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) spread through New York City with a little help from private homes. The role of households in how this virus spreads has never been analyzed in this manner before.

MRSA is infamous for spreading through the harshest environments, for being extremely resilient to antibiotics and other classes of drugs, and for enduring even on sterilized hospital equipment and devices. The bacterium prefers attacking people with a weak immune system, such as those on ventilators and other life-support instruments, and is oftentimes incurable.

For this study, the team analyzed a MRSA strain designated USA300, which can be found in public spaces – including gyms and hospitals – in New York City. The team was especially interested to learn how this bacterial strain traveled between Manhattan and the Bronx, two large NYC neighborhoods. The study is detailed in the April 21 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This research could be of great use to other epidemiological investigations trying to assess how MRSA and other opportunistic bacteria and viruses colonize new communities and environments. What this work does is basically provide a framework on how to study these migrations, the team explains.

USA300 was selected for this research because it accounted for three quarters of all skin and soft-tissue MRSA infections in northern Manhattan, back in 2009. A total of 400 MRSA isolates were investigated and their genomes sequenced. The samples were collected between 2009 and 2011 from 161 people diagnosed with infections. The readings were then compared to those collected from healthy people.

All this information was then correlated with each participant's medical records, antibiotic usage patterns, and their location. “This is an elegant and productive use of whole genome sequencing in an epidemiological investigation,” comments Alexander Tomasz, a microbiologist at the Rockefeller University in New York who was not involved in this investigation.

Uhlemann's team focused on determining the rate at which MRSA USA300 accumulated tiny changes in its genomes, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). The results of their analysis revealed that the last common ancestor between USA300 and its progenitor MRSA strain lived around 1993, which means that the two are separated by countless generations, Nature News reports.

The team found that MRSA strains from Texas and California also united with the NYC strain at some point, and now argues that USA300 did not spread throughout the city from a single source. Rather, it was brought here on multiple occasions, each of which represented a point of dissemination.

An interesting finding was that individuals living in average households appeared to exchange MRSA strains quite often. “There were some households where we found multiple kinds of USA300, which is quite surprising. It suggests some kind of outside reservoir, such as a link to a hospital or a gym,” Uhlemann concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //