Every year, thousands of people in hospitals around the world get infected with opportunistic microorganisms such as the Clostridium difficile bacterium. The effects of these hospital-acquired infections even lethal, but a new vaccine against the organism may be on its way.

One of the things that need to be kept in mind about this bacterium is that it's an antibiotic-resistant pathogen. This means that it's no longer sensitive to conventional antibiotics, doctors explain.

But Germany investigators Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces (MPICI), in Potsdam, have just finished coordinating an international research effort for synthesizing a new chemical to fight this dangerous bacterium.

The microorganism causes serious gastrointestinal diseases, and it mostly affects cancer or HIV patients. All those with weak immune systems are also predilect targets. Disinfecting large buildings that house thousands at a time is not really possible, scientists add.

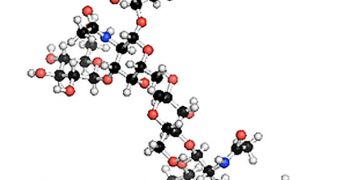

In the new research, experts used a sugar-based vaccine to destroy C. difficile. In mice models, the chemical caused a swift, specific and effective immune response. The results showed promise that they might be translated to human subjects as well.

In the general population, C. difficile affects only about 4 percent of all people. However, healthy immune systems limit the extent to which the microorganism can damage the host that carries it.

But, in hospital patients, infection rates increase to anywhere between 20 and 40 percent, statistics show. In people who take antibiotics that destroy their intestinal flora, C. difficile multiplies itself with extreme rapidity.

But a cure is coming, experts say. “Initial testing of the sugar-based antigen synthesised by the team has already produced very promising results,” explains the director of the MPICI, Peter H. Seeberger.

“The fact that mice are producing antibodies against the carbohydrates is in itself a success. Not all carbohydrates trigger the production of antibodies,” he goes on to say, referring to the sugar-like substance from which the new vaccine is produced.

The team says that the newly-developed antigen will not cause autoimmune diseases. “We can therefore expect to see that the human immune system produces antibodies against the sugar when vaccinated,” Seeberger says, quoted by AlphaGalileo.

“Since the natural sugar already elicits the production of a small number of antibodies, we hope that the synthetic glycoprotein conjugate will trigger a more effective response,” Peter H. Seeberger says.

“If these tests are successful, it will probably still take one or two years before the vaccine is tested on humans,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //