Thanks to unyielding efforts made by scientists operating two experiments on the world's most powerful particle accelerator, physicists are now able to say with a high degree of certainty that the prospective mass range in which the Higgs boson may be hiding is constantly shrinking.

According to the scientists, the elementary particle is running out of places to hide. However, investigators need to push on, considering the significance that finding this particle would have on science and the Standard Model.

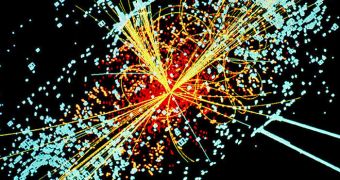

Physicists with the ATLAS (A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS) and CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) detectors on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have over the past couple of years severely limited the energy range in which the Higgs might be hiding.

Obviously, their goal is to close the gap and find the elusive particle, which is the primary reason why the 27-kilometer particle accelerator was built in the first place. The LHC can be found deep underground, alongside the French-Swiss border, near Geneva.

“Each time we add new data to our analyses, we close in more on where the Higgs might be hiding,” University of Florida professor and deputy physics coordinator for the CMS experiment Darin Acosta said earlier this year at a conference.

The meeting, called the biennial Lepton-Photon conference, took place earlier this year in Mumbai, India. LHC experts presented a series of papers, including one that showed the Higgs is not located between energy levels of145 to 466 gigaelectronvolts (GeV).

Experts told attendants that these results are 95 percent certain. This means that there is still a 5 percent chance the particle is hiding within this energy range, having eluded capture by the most advanced experiment ever constructed in the world.

“We have the Higgs cornered, and if the LHC continues to perform as it has over the past several months, by early next year the Higgs won't have much room to hide anymore,” added University of Oregon Knight Professor of Natural Sciences and physicist Jim Brau, in an email.

“The more data the experiments collect, the more scientists can say with greater statistical certainty. The LHC has been providing that data at an impressive rate. The machine has been functioning beyond expectations,” adds expert Konstantinos Nikolopoulos.

The physicist holds an appointment with the US Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), and is assigned to the ATLAS experiment. A total of 1,700 scientists, graduates students and engineers of the 3,000+ working at the LHC come from the United States.

The American involvement is sponsored by the DOE Office of Science and the US National Science Foundation (NSF), through funds awarded to the BNL for the ATLAS experiment and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory for the CMS experiment.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //