Just when scientists thought they understood the broad lines of planetary formation, a new study comes to place new doubts on established theories. The research argues that either planet-bearing stars are more common than thought, or planets form much quicker than other theories suggest.

The paper, published in the July 5 issue of the top scientific journal Nature, is authored by experts at the University of Georgia (UGA), University of California in San Diego, University of California in Los Angeles, California State Polytechnic University and the Australian National University.

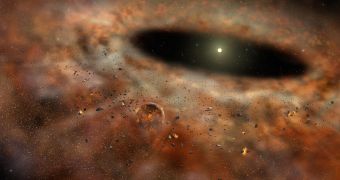

According to the joint team, the research was set into motion by the fact that the protoplanetary disk surrounding a very young star located in the Scorpius-Centaurus stellar nursery disappeared entirely from view in just three years.

Until now, astronomers believed that it takes millions of years for the dust inside such rings to clump up around gravity centers, and then slowly accumulate mass as they grow into planetoids, protoplanets, and ultimately fully-fledged planets.

Yet, this is what telescope measurements are revealing now. “The most commonly accepted time scale for the removal of this much dust is in the hundreds of thousands of years, sometimes millions,” explains Inseok Song, a coauthor of the Nature paper.

“What we saw was far more rapid and has never been observed or even predicted. It tells us that we have a lot more to learn about planet formation,” adds the expert, who holds an appointment as an assistant professor of physics and astronomy in the UGA Franklin College of Arts and Sciences.

According to measurements of this protoplanetary disk, the formation had enough dust to completely fill out the inner solar system, from the Sun's surface to the orbit of Mars. That's a lot of dust.

The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) was the first to observe the disk around the star TYC 8241 2652 1. The formation gave off the unmistakable IR signature of protoplanetary rings. A Gemini South Observatory image collected in mid-IR wavelengths in 2008 revealed no signs of the structure.

Not even the European Space Agency's (ESA) Herschel Space Observatory, the most advanced space telescope ever created, could find the disk, in spite of using its state-of-the-art Photodetector Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS) instrument.

“It's as if you took a conventional picture of the planet Saturn today and then came back two years later and found that its rings had disappeared,” adds UCLA investigator and world-renowned protoplanetary disk expert Ben Zuckerman, also a coauthor of the new study.

The research was made possible through funds from the US Department of Energy's (DOE) Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), the National Science Foundation (NSF) and NASA.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //