Pigs are not just for ham; indigenous pigs can trace the origin of the people that raise them.

DNA analysis of wild and domestic pigs has made archaeologists change the ideas of where the Malayo-Polynesian colonists originated and which their migration routes were so that they reached the remote Pacific islands.

Researchers from Durham University and the University of Oxford, investigating DNA and tooth morphology in modern and ancient pigs, have made discoveries in direct contradiction to the old idea that Malayo-Polynesian colonists may have originated in Vietnam and sailed between numerous islands before first reaching New Guinea, and later landing on Hawaii and French Polynesia.

Mitochondrial DNA, achieved from modern and ancient pigs across East Asia and the Pacific, revealed that a particular genetic pattern is shared by modern Vietnamese wild boar, modern feral pigs on the islands of Sumatra, Java, and New Guinea, ancient Lapita pigs in New Caledonia, and modern and ancient domestic pigs on some Pacific Islands.

Previous models stated that the ancient migration of the ancestors of Pacific islanders originated in Taiwan or islands Southeast of Asia (like Sumatra, Borneo, Java), and traveled through the Philippines as they spread into the remote Pacific. "Many archaeologists have assumed that the combined package of domestic animals and cultural artifacts associated with the first Pacific colonizers originated in the same place and was then transported with people as a single unit. Our study shows that this assumption may be too simplistic, and that different elements of the package, including pigs, probably took different routes through Island South East Asia, before being transported into the Pacific", said research project director, Dr Keith Dobney, a Wellcome Trust senior research fellow with the Department of Archaeology at Durham University.

Archaeological proofs showed that early farmers migrated from mainland East Asia through Island Southeast Asia and on into Oceania, carrying with them their domestic plants, animals (dogs, pigs and chickens) and specific pottery styles with them.

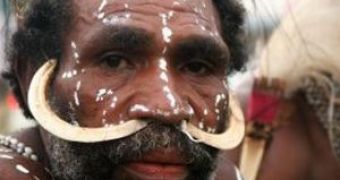

We have to underline the fact that the Malayo-Polynesians were not the first human populations in the entire Pacific. Indeed, in what is called Polynesia and Micronesia they were the first inhabitants, but in Melanesia they met a pre-existent Melanesian race (Asian Blacks, like in New Guinea or Southern India).

Melanesians were found in New Guinea, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Fiji, Solomon, and in fact, in all islands of southeastern Asia (Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Sulawesi, Lesser Sundas) and mainland southern Asia before the massive immigration of Mongoloid populations of farmers-gatherers. (in fact, the proper Malayo-Polynesians are a mix of Mongoloids with Black Asians as you can easily see on the Hawaiian or Maori - from New Zealand - faces.)

It is likely that before the Malayo-Polynesian migration, which introduced farming in all the Pacific islands, Melanesians were just hunters-gatherers. Even today, most Melanesians speak Malayo-Polynesian languages, even if their physical type was less affected by this migration.

Human genetic and linguistic data suggests that the Malayo-Polynesian colonists first began their journey in Taiwan. "Pigs are good swimmers, but not good enough to reach Hawaii. Given the distances between islands, pigs must have been transported and are thus excellent proxies of human movement. In this case, they have helped us open a new window into the history of human colonization of the Pacific. We are confident that this research will inspire geneticists and archaeologists to consider both alternative colonization routes, and more complex, and perhaps more accurate, theories about the nature of human colonization and the animals they carried with them", said Greger Larson, lead author of the research, who made the genetic analysis at the University of Oxford.

The specimens employed in these analyses resulted from the jawbones or teeth of museum and archaeological specimens and hair samples from more recent specimens.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //