Boats and ships have been used by man to ferry people and cargo across large bodies of water for millennia, but there are still some things that just can't be done, or at least not easily. One of them is controlling waterborne objects from afar.

When you're piloting a boat or ship, it's easy enough to get it to go where you need it. Back when we still used wind sails it was doable, but now, with engines involved, it's a lot easier, and safer too, especially during storms.

However, if you're trying to send out a buoy or retrieve something from the waters, things get trickier. Usually, it means someone has to go out in a boat and tow it in.

It can be especially frustrating and dangerous during rescue operations. Say a boat is scuttled and you're there to retrieve the survivors. Any time lost can mean death, especially if the water is colder than healthy.

Tractor beams are still the stuff of science fiction, but researchers from the Australian National University managed to create something that has a similar outcome.

Basically, they forewent the idea of gravity manipulation, or whatever principles are expected to eventually enable actual tractor beam technology.

Instead, they decided to control the water currents themselves. A system created complex 3D waves that had their very own currents. Essentially, it lets you adjust wave sized and frequencies.

With control over this, you can produce any sort of water flow, allowing you to pull in people and flotsam or make vortices on demand for whatever reason.

It doesn't even have to be debris or lifeboats. A 3D wave generator could help bring small boats into ports, contain oil spills without using chemicals (or burns and barriers), simulate challenging sea conditions for training purposes, etc.

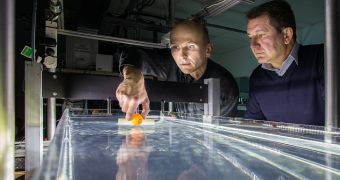

You can see the technique in action in the video embedded below. A ping-pong ball was placed in a wave tank and helped work out the size and frequencies of the waves needed to tow it in.

There are no practical applications possible yet, mostly because there is no mathematical theory that can explain these experiments, according to Dr. Horst Punzmann from the Research School of Physics and Engineering, who led the project.

Currently, the scientists are testing both waves and swirling flow patterns created with the aid of differently shaped plungers. We will return with an update whenever something more comes of this initiative, though it may take months. In the meantime, maybe someone will try to do this with wind.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //