One of the most severe effects of global warming, and the climate change it produces, is the thawing of permafrost, the perennial-frozen soils located in Arctic regions. These lands contain vast amounts of greenhouse gases, which could be released in the atmosphere by the end of this century.

Calculations show that billions of tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane are trapped inside permafrost. This type of soil is filled with organic matter, which decays to form these gases. However, the frozen crust at the surface has been keeping them trapped for years.

At this time, global warming is exerting a great deal of pressure on these area, making them hotter than they normally would be. This leads to the melting of the permafrost, which in turn allows for dangerous GHG to escape into the atmosphere.

By the end of the century, scientists now estimate, billions of tons of CO2 and methane could be released from their Arctic prison, accelerating global warming, and creating a vicious circle from which there is no escape.

Under these circumstances, the need for action becomes even more dire, although politicians and businesses do not appear to be convinced by these necessities. By the end of the 21st century, the permafrost might become a source, rather than a sink, for greenhouse gases, especially CO2.

The study that revealed this trend was carried out by scientists at the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), who were led by Charles Koven.

“Previous models tended to dramatically underestimate the amount of soil carbon at high latitudes because they lacked the processes of how carbon builds up in soil. Our model starts off with more carbon in the soil, so there is much more to lose with global warming,” Koven explains.

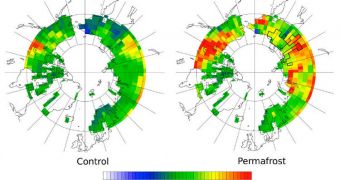

“Including permafrost processes [in climate models] turns out to be very important,” adds the expert, who is a staff scientist with the Berkeley Lab Earth Sciences Division since earlier this year.

Details of the new research appear in a paper published in last week’s early online issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

As opposed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2007 fourth assessment report, the new model starts with a lot more carbon in the soils, since the chemical's formation processes were also included in the simulation.

This led to more severe outcomes than the ones the UN group produced. The DOE Office of Science, the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, in France, and the European Union project COMBINE provided the funds for this study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //