Selective laser sintering (SLS) has been used for 30 years now as a manufacturing technology, but it may be upstaged, if not altogether replaced soon, by a new technique called high-speed sintering, or HSS for short.

A team of scientists from the University of Sheffield have developed a new 3D printing method that can quickly and efficiently build items with multiple characteristics at different points.

In other words, humans now have control over the density of the material at various stages of production and, thus, in various parts of whatever object is being constructed.

Normally, in an SLS process a laser selectively melts a powdered metal one layer at a time, after which a second layer of powder is added and the process is repeated.

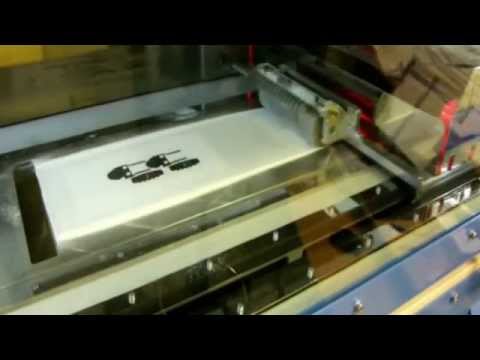

In HSS, however, it's not a metal powder that is used, but a specialized heat-sensitive ink made of carbon. An inkjet printer is tasked with adding layers of carbon black ink, in the exact shape of whatever object is being constructed.

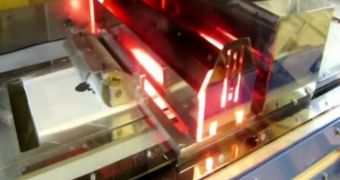

After each layer is added, an infrared lamp bathes the build bed in radiation, causing the ink-soaked powder to melt (since it receives more energy faster, as carbon black absorbs infrared radiation quickly).

Not exactly a new technology really, but what Sheffield researchers have discovered is that they can perfectly control the density of the 3D printed objects, and even make sure different parts have different densities.

How? By controlling the shade of grey that the ink comes in. The grey/black shade is dictated by the amount of carbon black ink used, you see, so researchers can print fewer black dots in order to get a lighter shade, or go the opposite way at will.

Until now, 100% black has been used, but mechanical properties of the material can reduce after a certain level. Based on observations, it was discovered how to get the best amount of strength at the lowest risk. From there, they could determine how to optimize the material used and give items different mechanical properties without using multiple materials during the construction.

Say you're making a part for an airplane or car and need the inside to be stiff and rigid, but the outside to be a bit more flexible, maybe smoother too. Same for, say, a shoe sole. You can do it using the same material now, instead of several different metals/alloys. So far, density differences have stretched to 40%. This not only enhances manufacturing options, but also saves a lot of money.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //