Over the last few years, numerous controversies have sprung up around massive particle accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Most often, critics fear that these giant machines will produce particle collisions that are so energetic that they could give birth to very small black holes. Physicists say that this is entirely probable, and that creating artificial black holes would be a major scientific achievement. But many fear that the structures would get out of hand, and gobble up the entire planet, and they have even petitioned the United Nations to put an end to the LHC.

Now, for the first time, a computer simulation shows that the scenario in which tiny black holes are produced under Einstein's famous theory of general relativity is entirely possible, and even likely. The respected physicist Albert Einstein said on several occasions that such an event is possible, but this is the first time this has been experimentally proven to be true. “I would have been surprised if it had come out the other way. But it is important to have the people who know how black holes form look at this in detail,” says physicist Joseph Lykken, who is based at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), in Batavia, Illinois.

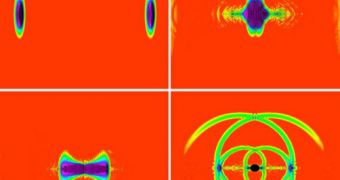

In a study published in the respected scientific journal Physical Review Letters, experts say that the computer model used in the new investigations took into account the forces of gravity that occur between two colliding particles, as well as advanced mathematical calculations referring to the general theory of relativity. ScienceNow reports that black holes can only form when particles collide at one-third of the fundamental limit known as the Planck energy. This data alone should put LHC critics at rest. The Planck energy is a quintillion (10^18) times higher than the particle accelerator's maximum energy output, which peaks at 7 Tev per beam, or 14 Tev combined.

“I would be extremely surprised if there were a positive detection of black-hole formation at the accelerator,” says expert Matthew Choptuik, from the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, Canada. Together with Princeton University colleague Frans Pretorius, he created the computer model that was used for these investigations. “It's a real tribute to their skill that they were able to do this through a computer simulation,” adds University of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB) gravitational theorist Steve Giddings. The bottom line is that, for now, we can rest assured that the possibility of black holes being created at the LHC is extremely small.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //