Cellulose has for a long time been touted as a material that is capable to provide the foundation for a new type of batteries, that could power up small applications. For instance, they could be used in gift wraps, that could light up and say “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Birthday.” But what physicists are more interested in is producing thin, flexible, and light-weight batteries, that can biodegrade over a period of time, leaving nothing of them behind. Obtaining such a power-storing device would enable multiple applications in nanotechnology, medicine, and entertainment, LiveScience reports.

Experts have also been looking for a way of replacing metallic components in batteries for a long time. Until now, the best bet were conducting polymers, although they obviously had some limitations. If used for extended periods of time, they would lose their ability to hold an electric charge, which essentially rendered them useless for any practical applications. But the new approach, which is based on cellulose extracted from the green algae Cladophora, promises to overcome these differences, while at the same time fulfilling all of the demands made by physicists and other specialists.

Cladophora is best known as one of the main culprits of making some beaches smelly and foul. The organisms look like strands of hair and are fairly harmless in themselves. However, currents push them together and they then become a nuisance to get rid of. They also release a number of foul-smelling compounds as they rot, usually on land. Now, researchers have found a way to make use of all this biomass, which would have otherwise simply gone to waste. An additional reason why this algae was selected is the fact that the type of cellulose it contains has a surface that is nearly 100 times larger than that of cellulose commonly found in paper.

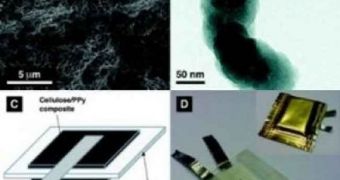

“We have long hoped to find some sort of constructive use for the material from algae blooms and have now been shown this to be possible. This creates new possibilities for large-scale production of environmentally friendly, cost-effective, lightweight energy storage systems,” explains Uppsala University nanotechnologist and researcher Maria Stromme. The batteries themselves are made of layer of conducting polymers, each some 40 to 50 nanometers thick, placed on either sides of a thinner layer of algae cellulose. “They're very easy to make,” Stromme reveals, adding that the batteries are cheap.

“When you have thick polymer layers, it's hard to get all the material to recharge properly, and it turns into an insulator, so you lose capacity. When you have thin layers, you can get it fully discharged and recharged,” adds Uppsala University electrochemist Gustav Nystrom.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //