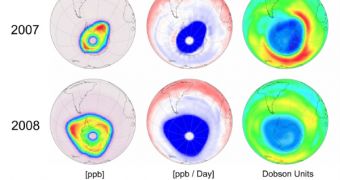

This year, the European Space Agency's (ESA) satellites and follow-up instruments recorded the second largest recorded hole in the ozone layer, second in size only to the one observed in 2006. While 2007 showed some promise in this regard, with an increase in the thickness of the layer, the tendency did not go on into this year as well. Meteorologists say that this is normal, considering that the factors influencing the ozone layer change considerably from year to year.

The ozone layer plays a crucial part in protecting life on Earth, as it shields the planet from harmful radiation and ultraviolet rays emanating from the Sun, which would otherwise cause severe burns and skin cancers in humans, as well as terrible damage to the marine wildlife, seeing how the oceans would become much hotter than they currently are and that many species would be unable to adapt to their new environment.

The hole above the Antarctic is currently more than 27 million square kilometers (16.7 million square miles) wide, showing a 2 million sq km (1.24 million sq miles) increase since last year. The layer stands at about 25 km (15.5 miles) into the atmosphere, but it's very responsive to cold temperatures and man-made substances such as chlorine and bromine, derived from chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). The production of these chemicals was banned by the Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, but they still linger in the upper layers of the atmosphere since before that time.

Scientists are now striving to determine how present and future environmental conditions will affect the ozone layer. Carbon and sulfur emissions are a very hot research subject, especially among European scientists working with the Envisat satellite system. "We want to know when the ozone hole will recover, how its recovery will be complicated by an environment with increasing greenhouse gases and how atmospheric dynamics will shape future ozone holes. These and many other questions will attract the attention of our generation of scientists for the next several decades," said Deborah C Stein Zweers, a researcher with the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //