A team of experts claims it manage to discover the oldest signs of biomineralization, the process through which some animals convert minerals into hard structures. All shelled creatures are capable of doing this, and now scientists say they may have found their common ancestor.

The microscopic organisms the team found are no less than 750 million years old, predating the Great Oxygenation Event that put oxygen into Earth's atmosphere by more than 200 million years.

This means that the creatures existed long before any of the species we see today were alive. It's only after the oxygenation event that enough oxygen was put into the planet's air to allow for the development of larger, more complex species.

But the new findings show that microorganisms were capable of biomineralization even before that time. Some of the most common byproducts of this process include bones, shells, teeth and hair.

Harvard University investigators Phoebe Cohen and Francis Macdonald were in charge of the research team, which removed the perfectly preserved fossils from an ancient rock formations in the Yukon Peninsula, Canada.

The finding provides experts with “a unique window into the diversity of early eukaryotes,” the researchers writes in a paper accompanying the discovery. The work is published in the June issue of the renowned scientific journal Geology.

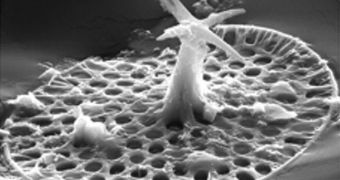

While analyzing hundreds of small fossils under a microscope, the experts determined that algae species known as Archeoxybaphon, Bicorniculum and Characodictyon were the most likely candidates to having former mineral shells during their lifetime.

In past studies, experts proposed that past organisms began producing shell-like structures to defend themselves against the environment some 750,000 million years ago, but they had no solid proof.

Other analysis of old fossils could not establish with certainty whether the minerals discovered in the microorganisms were of a biological origin or not. In the new work, this was proven with certainty.

According to experts, biomineralization may have appeared as a response to predation, which is known to have been extremely fierce in the world of single-celled organisms. If some covered themselves with hard minerals, then their predators wouldn't have been able to eat them anymore.

The same line of reasoning may have held true for why bones appeared in more complex animals, comments University of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB) paleontologist Susannah Porter, quoted by Wired.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //