Gregory Ryskin, a physicist and researcher at the Northwestern University, is part of a growing group of researchers who are currently advocating the hypothesis that the magnetic poles of the planet are actually being pushed around by oceanic currents. When this idea first appeared, a large controversy ensued, and it continues to this day, but the number of researchers that has come to consider this theory to be true has increased several times over since that time.

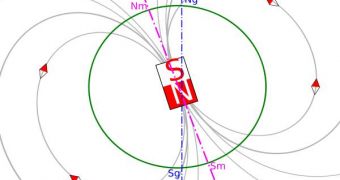

Most geophysicists believe that the locations and movements of the planet's magnetic poles, which are significantly different – as far as locations go – from the geographical ones, are determined by the influence of the planet's molten core, and also by the streams of magma moving under the Earth's crust. While some researchers believe that the idea is entirely stupid, to say the least, others consider that at least it's worth investigating, NewScientist reports. Ryskin believes that the oceanic currents may be carrying the magnetic fields along weak magnetic lines that they themselves generate.

“The oceans almost certainly slightly modify the geomagnetic field observed at the surface due to electric currents flowing within the Earth and in the ionosphere. Geophysicists would be in Ryskin's debt if he could improve on what others have already done. I wish him well,” Imperial College London (ICL) Geophysicist Raymond Hide said. Not everyone considers the work that Ryskin and others are doing a complete waste of time, and supporters say that it may be in science's best interest to analyze all the options of explaining a complex phenomenon such as the magnetic pole migration.

In his research, Ryskin was able to prove that the areas on the globe where the movements of the magnetic field were the strongest corresponded to the same places where the oceanic currents were strongest too. In addition, the researcher believes that, as oceanic water flows, it generates weak electric currents inside the planet's magnetic fields, which could, in turn, create secondary “oceanic” magnetic fields. He has also included these numbers in his calculations.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //