Over the past few years, numerous studies have sought to gain more insight into how microorganisms living in the world's oceans affect the global climate, by regulating Earth's carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycles, among others.

One of the most peculiar things about these organisms is that they appear to start behaving like larger, more complex creatures, when they are exposed to elevated levels of the chemical sulfur.

This is very interesting when considering that the global ocean engages in complex and, truth be told, little understood gas exchanges with the atmosphere. The gases that are exchanged the most have a lot to do with global warming and climate change, and this makes related studies critical to our future.

Overall, oceanic microorganisms play a critical role in regulating the cycle of important elements, but scientists have yet to agree on just how much influence these tiny life forms have on Earth's climate.

As such, a lot of emphasis is now being placed on understanding how the individual bacteria or microbe in the water exchanges chemicals with the environment. These data can then be extrapolated to larger scales, scientist believe.

This is also the focus of a new international investigation, which was led by a team of experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Led by professor Roman Stocker, the scientists looked at how particular strains of marine microbes seek out, find, engulf, and then process sulfur, before releasing it back into the ocean in altered form.

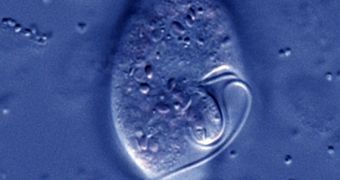

The group tracked down single-celled microbes using an observations technique known as video microscopy, to learn how they interact with two basic forms of sulfur.

The first, called dimethylsulfide (DMS), is the compound responsible for the slightly sulfuric smell that seas and oceans have. The second, dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), is the precursor of the former.

DMS is a very important chemical for Earth's atmosphere. When microbes that produce it release the gas into the atmosphere, DMS goes on to form cloud condensation nuclei, around which rain clouds form.

In addition to bringing water over land masses, these clouds also reflect back sunlight, preventing the Sun from heating up our planet beyond acceptable thresholds.

Details of the new investigation are published in an issue of the top journal Science, that appeared earlier this year. The work was funded in part by the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

Other contributors included the Australian Research Council, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, La Cambra de Barcelona, the Hayashi Fund at MIT.

“It had been previously demonstrated that DMSP and DMS draw coral reef fish, sea birds, sea urchins, penguins and seals, suggesting that these chemicals play a prominent ecological role in the ocean,” Stocker explains.

“Now we know that they also attract microbes. But this is not simply adding a few more organisms to that list,” he adds.

“The billions of microbes in each liter of seawater play a more important role in the ocean’s chemical cycles than any of the larger organisms,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //