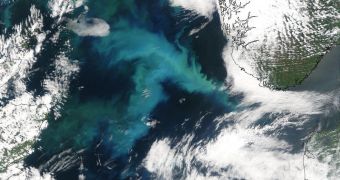

Experts are currently trying to get approval for the construction of a new series of Earth-sensing satellites, that would be capable of observing how the ocean changes color depending on season and other factors.

At this point, this is accomplished via three NASA satellites capable to tracking down plant life taking place in the oceans, but all of these spacecrafts are currently reaching the end of their lifespans.

One of them, called the SeaWIFS, has been flying for more than 13 years, even though it was originally planned to remain airborne for 3 to 5 years.

The other two satellites, called Aqua and Terra, have also exceeded their planned lifespan, so researchers operating them have no way of knowing how much more they will last.

One of the main disadvantages of operating these satellites is the fact that they have to be pointed at the Moon once every month, so that scientists can recalibrate the color-sensing instruments.

“If you’re looking at long-term changes, you need to know how your instrument is changing,” explains the chief scientist of the SeaWiFS, Charles McClain, quoted by Wired.

“The best way to do that is to roll the space craft a little bit to look at the Moon. It’s easy to do, but it interferes with operations. We’ve put a request in for NPP to it, but it hasn’t been approved,” he adds.

The NPP is bound to launch in 2011, and is being constructed by NASA, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Department of Defense (DOD).

Its name stands for the National Polar Orbiting Environmental Satellite System Preparatory Project.

The next alternative experts have for placing another ocean-observing satellite in orbit is to wait for the PACE mission, which is currently scheduled to take place in 2018.

“Operational satellites have to be replaced and have follow-ons, whereas scientific missions go up to see what they can see, and don’t necessarily have to have a follow on.This is really gravy for them, having their science collected on an operational satellite,” says Leo Andreoli.

The expert is a chief atmospheric scientist at the Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems. The company is one of the main contractors for satellite construction in the United States.

“I will say that being in the operation of satellites for many years that one does not like to take the satellite and turn it away from the earth because there is a risk you won’t be able to get it to turn back,” the expert adds.

This “needs to be weighed against the value of the mission,” he adds. The plan right now is to use some of NPP's secondary capabilities to keep an eye on chlorophyll in the oceans, until PACE is launched.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //