Over the past few years, numerous and important advancements have been made in the battery industry, with scientists developing ever smaller and more effective devices for a wide range of applications. In fact, it was progress in the industry that allowed car manufacturers to ponder releasing all-electric vehicle lines in the near future. But now, the innovation row is nearing its end, and scientists are already looking for the next best thing, which is, of course, a safe, light, and reliable nuclear-power source.

Scientist at the University of Missouri-Columbia (UMC), who are actively engaged in this line of research, say that their investigations were triggered by the fact that some of the batteries used at the moment had reached a point where they were larger and heavier than the very objects they powered up. “To provide enough power, we need certain methods with high energy density. The radioisotope battery can provide power density that is six orders of magnitude higher than chemical batteries,” UMC Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Jae Kwon explains.

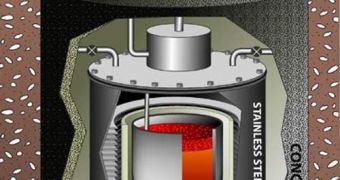

Powering handheld devices of prosthetics, for instance, with nuclear energy may not seem like the safest bet at first, the team says, but the safety concerns for its new power sources are minimal. It has been working for a long time to create a small, penny-sized nuclear battery, able to power various micro/nanoelectromechanical systems (M/NEMS), something that conventional batteries simply couldn't do. “People hear the word 'nuclear' and think of something very dangerous. However, nuclear power sources have already been safely powering a variety of devices, such as pace-makers, space satellites and underwater systems,” the expert shares.

An additional innovation that has been integrated in the new nuclear battery is that, rather than using a solid semiconductor, the power source employs a liquid one. “The critical part of using a radioactive battery is that when you harvest the energy, part of the radiation energy can damage the lattice structure of the solid semiconductor. By using a liquid semiconductor, we believe we can minimize that problem,” Kwon adds. Details of the batteries appear in two scientific publications – the Journal of Applied Physics Letters and the Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //