Climatologists draw attention to the fact that a relatively new, yet-unstudied type of El Nino is making its presence felt more and more in the world, with potentially significant implications for climate change patterns.

Researchers say that this El Nino warms water in the central-equatorial Pacific Ocean, a fact that is highly uncommon for such an event.

Usually, the atmospheric phenomenon was directly responsible for heating up the waters in the eastern-equatorial Pacific Ocean. Analyzing the changes may provide us with additional clues as to how El Nino events interact with global warming.

Experts also want to determine which of the two is the driving force, and which is the fact, Such data could help us develop better mitigation efforts against the effects of global climate change.

This new type of events, affecting the eastern-equatorial Pacific, is becoming increasingly common and progressively stronger, which has researchers wondering as to what the cause might be.

Researchers at NASA and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently announced the results of a new study they conducted on the issue, which confirmed previous measurements collected by other research groups.

The scientists who conducted the research looked at records of El Nino intensity stretching back to as far as 1982. NOAA satellite observations of sea surface temperatures were also combined in the study.

The work was led by expert Tong Lee, who is based at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California and scientist Michael McPhaden, from the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, in Seattle.

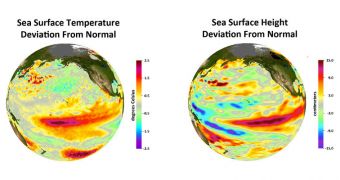

The two experts say that the strength or intensity of each El Nino event was derived from direct and satellite-based measurements of sea surface temperatures. Each deviation from the long-term average was recorded, the two experts say.

“Our study concludes the long-term warming trend seen in the central Pacific is primarily due to more intense El Ninos, rather than a general rise of background temperatures,” Lee explains.

“These results suggest climate change may already be affecting El Nino by shifting the center of action from the eastern to the central Pacific,” McPhaden says.

“El Nino's impact on global weather patterns is different if ocean warming occurs primarily in the central Pacific, instead of the eastern Pacific,” he adds.

“If the trend we observe continues, it could throw a monkey wrench into long-range weather forecasting, which is largely based on our understanding of El Niños from the latter half of the 20th century,” McPhaden concludes.

Details of the new investigation were published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //