For some people, such as smokers or those who've suffered violent accidents, a lung transplant may be the only chance they have of living. But oftentimes their lives are cut short by a deadly disease, called bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). Experts have now developed a new defense against it.

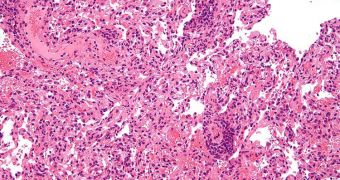

The debilitating and fatal condition acts by clogging up the lungs and adjacent airways with scar tissue, which in turn diminishes the lungs' ability to process air and exchange gases, ultimately leading to suffocation and death.

Fighting BOS has been an objective for experts for many years, but thus far their struggle has proven fruitless. Even today, that goal is far from being achieved, scientists say.

But a team from the University of Michigan brings a ray of hope for people who got their lungs transplanted, in the form of a new technique for the early detection of BOS symptoms.

By using this method, healthcare experts hope to be able to identity the patients in which BOS is developing when the disease is still in its earliest stages. This enables surgeons to intervene fast, and treat the condition before it becomes life-threatening.

Ultimately, the end goal of the research is to use this tool as a basis for a new variety of treatments against this disease. If this objective is achieved, then thousands of lives should be spared.

Official statistics show that about 50 percent of all lung transplant receivers will develop BOS within five years of receiving the new organs. Among those who die following the transplants, BOS is the leading cause of death within the first year.

U-M Medical School assistant professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine Vibha Lama, MD, MS, led the team that discovered a very interesting fact – the more stem cells patients have in the lungs half a year after the surgery, the more likely they are to develop the disease.

“Our study provides the first indication of the important role these cells play in both human repair and disease. It’s very important from the clinical perspective because we didn’t previously have any strong biomarkers for BOS,” the expert explains.

“By the time we usually diagnose BOS, there’s already been a huge decline in lung function. If we can find the disease early, we can potentially do something about it,” Lama says of the importance of having a biomarker for BOS, Science Blog reports.

The new research was supported with grant money from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Thoracic Society and the Scleroderma Research Foundation.

Additional contribution were made available by Brian and Mary Campbell, and Elizabeth Campbell Carr. Details of the work were published online in the latest issue of the esteemed American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //