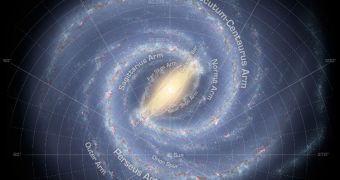

In a finding that could help scientists get new insight into how our galaxy is made up, and what chemicals form its basis, researchers recently managed to identify new stellar nurseries in the Milky Way. These are regions of intense stellar formation, which churn up young, blue stars at regular intervals. These celestial fireballs are derived from giant clouds of cosmic dust and gas, which at one point collapse under their own weight, igniting in the process. The newly-found data suggests that the Milky Way is a lot more active than originally thought, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) reports. The organization is a facility of the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

“We can clearly relate the locations of these star-forming sites to the overall structure of the Galaxy. Further studies will allow us to better understand the process of star formation and to compare the chemical composition of such sites at widely different distances from the Galaxy's center,” explains Boston University professor and study researcher Thomas Bania. The expert presented the new findings a couple of days ago, at the 216th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS 2010), held in Miami, Florida.

A team of experts from NRAO, led by scientist Dana Balser, and a group of French investigators from the Astrophysical Laboratory of Marseille, led by expert Loren Anderson, also contributed to the research. The scientists explain that what they were looking for were very specific stellar nurseries called H II regions. Inside these cosmic structures, hydrogen atoms in cosmic gas are generally left without their electrons. The elementary particles are ripped apart by large radiation winds, triggered by the activity of young massive stars in the vicinity. These influences leave a specific signature, experts say.

“We found our targets by using the results of infrared surveys done with [the] NASA Spitzer Space Telescope and of surveys done with the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope. Objects that appear bright in both the Spitzer and VLA images we studied are good candidates for H II regions,” Anderson says. The extremely-sensitive Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) was ultimately used to confirm the findings.

The star-forming regions the astronomers sought, called H II regions, are sites where hydrogen atoms are ionized, or stripped of their electrons, by the intense radiation of the massive, young stars. To find these regions hidden from visible-light detection by the Milky Way's gas and dust, the researchers used infrared and radio telescopes. “Finding the ones beyond the solar orbit is important, because studying them will provide important information about the chemical evolution of the Galaxy. There is evidence that the abundance of heavy elements changes with increasing distance from the Galactic center. We now have many more objects to study and improve our understanding of this effect,” Bania concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //