An international team of researchers recently conducted a new study on the vast plastic debris fields that scar the world's oceans. During their investigation, they found an entirely new group of microbes in plastic flotsam, which does not survive anywhere else on Earth.

The experts say that this conclusion is only a taste of what phenomena such as global warming and climate change will bring to the world in the near future. The microbes are even more mysterious since they appear to have developed a knack for consuming plastic.

With this discovery, scientists have proved with great certainty that even artificial structures such as this garbage patches can create stable ecosystems and habitats where none was before.

This new world the research team discovered has been collectively called the plastisphere. Details of how it works, and how species interact within it, appear in the latest issue of the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Until now, studies of oceanic garbage patches have concentrated exclusively on the effects that plastic particles in the water have on larger species, such as fish and birds. The international team behind this work was the first to look at how the plastisphere promotes the development of life.

The research was conducted in the northern sector of the Atlantic Ocean. The group sampled ocean water from numerous sites, and collected pieces of plastic between 1 and 5 millimeters in diameter. They found microbial communities on these shards that were unlike others in the surrounding waters, ABC reports.

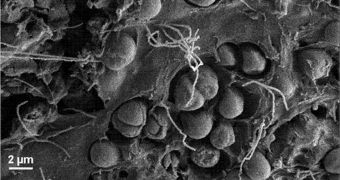

The discovery was made using a combination of high-resolution imaging and genetic sequencing. The research team included experts Tracy Mincer from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, and Linda Amaral-Zettler, from the Marine Biological Laboratory.

“The organisms inhabiting the plastisphere were different from those in surrounding seawater, indicating that plastic debris acts as artificial 'microbial reefs.' They supply a place that selects for and supports distinct microbes to settle and succeed,” Mincer explains.

Overall, the study found in excess of 1,000 species of microbes living on plastic in the ocean. Several types of plants, algae and bacteria have also been discovered, many of them new to science.

“We're not just interested in who's there. We're interested in their function, how they're functioning in this ecosystem, how they're altering this ecosystem, and what's the ultimate fate of these particles in the ocean,” Amaral-Zettler concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //