NASA microbiologists announce the a hardy microbe has been discovered in not one, but two of the agency's clean rooms, in both Florida and South America. The finding is very interesting because no species or genus of clean room microbe has ever been found in two different quarantine facilities.

When assembling spacecraft for deep-space or planetary exploration, NASA engineers always observe protocols that seek to avoid contaminating other worlds with lifeforms from Earth. As such, the probes and satellites are assembled in clean rooms, where harsh disinfection techniques are applied.

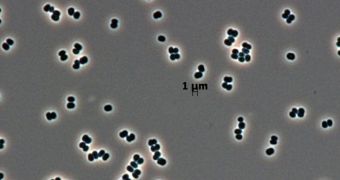

While the overall number of microbes is extremely small, the processes used for sterilization also play a role in selecting among the toughest types of microorganisms. As such, the lifeforms that do survive ultraviolet radiation, chemical treatments and tremendous heat are extremely resilient.

Ironically, the microbes that endure in clean rooms are also more likely to be able to withstand the harsh conditions of space, if they make their way onto spacecraft. NASA microbiologists periodically swab the nooks and crannies of clean room in a bid to catalog all surviving microbes.

During such a study, conducted in 2007 when the Phoenix Mars Lander was being assembled, researchers stumbled upon a hardy microbe now called Tersicoccus phoenicis. The organism was found at the NASA Kennedy Space Center (KSC), in Florida.

The new investigation also found T. phoenicis in a clean room at Kourou Spaceport, which the European Space Agency (ESA) operates in French Guiana. The two facilities are more than 4,000 kilometers (2,500) miles apart.

“We want to have a better understanding of these bugs, because the capabilities that adapt them for surviving in clean rooms might also let them survive on a spacecraft. This particular bug survives with almost no nutrients,” Parag Vaishampayan says.

The expert is a microbiologist with the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, California, and also the lead author of the new paper on T. phoenicis. He was able to find the microbe by browsing through the international bacterial DNA database that space agencies keep in order to monitor the microbes that might end up in space.

This database is an effective way of cross-referencing potential discoveries of life on other planets. For example, if a spacecraft returns carrying unknown organisms, microbiologists will be able to check their DNA for signs to prove that they are in fact modified versions of clean room microbes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //