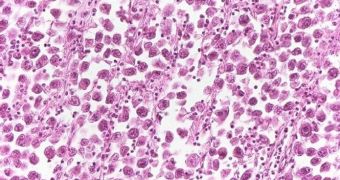

Scientists at the Universities of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB), San Diego (UCSD) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have recently developed a potent mix, or cocktail, or various types of nanoparticles, which is extremely apt at targeting and destroying cancer tumors. The group reports that the innovation shows great promise in battling cancer, and that it may one day become a standard therapy in hospitals around the world. The particles the new system uses are able to work in tune with the immune system, so as to provide the most effective results possible.

“This study represents the first example of the benefits of employing a cooperative nanosystem to fight cancer,” UCSD Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Michael Sailor explains. He is also the primary author of a new paper detailing the amazing findings, which will appear in an upcoming issue of the respected journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The work was already detailed in an online issue of the publication that appeared last week. UCSD contributed chemistry experts, MIT bioengineers designed the new system, and UCSB experts constructed it.

According to the group, the innovation consists of two types of nanoparticles that are able to work in concert to deliver the most devastating blow possible to tumorous cancer cells. The first of the two components is designed specifically for the “search” part of the mission. Its job is to navigate the immune system and to find where tumors or other cancer cells reside. The second component then steps in, and deals with the troublesome cells themselves. Its primary role is to destroy, and the team reveals that they cannot navigate through the body except when attached to the first particles. Both types of nanostructures are several thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair.

“[...] A nanoparticle that is engineered to circulate through a cancer patient's body for a long period of time is more likely to encounter a tumor. However, that nanoparticle may not be able to stick to tumor cells once it finds them. Likewise, a particle that is engineered to adhere tightly to tumors may not be able to circulate in the body long enough to encounter one in the first place,” MIT Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research expert Sangeeta Bhatia explains. The scientist, who is also a coauthor of the new PNAS paper, is a physician, bioengineer and professor of health sciences and technology at the Institute. He is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

“This study is important because it is the first example of a combined, two-part nanosystem that can produce sustained reduction in tumor volume in live animals,” Sailor concludes. The project was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //