We've seen and heard about plenty of semi-technological substitutes for actual body parts, and parts of body parts. Implants is the general term for such things. Soon, though, the line between implants and transplants will blur.

A transplant is when a person gets a new finger, kidney, liver, heart or something else donated by another person, or harvested from a newly deceased person. As macabre as it sounds, people who die in accidents are the prime source of heart transplants.

In an ideal world, though, no one would actually die from an accident, or anything else. That means that people who do suffer from ailments that push for a transplant wouldn't have anything to get as transplant.

Naturally, no one will ever advocate the cessation of progress just so transplants wouldn't run out (not openly anyway).

That means that synthetic or partially synthetic alternatives need to be created, at least until we eliminate crimes and accidents (fat chance).

The new way to 3D print cartilage

Cartilage is believed by many biochemists and biomechanical engineers to be the substance that will be ready for use in humans the soonest.

Meanwhile, 3D bioprinting has been making significant strides of its own, to the point where some universities offer graduate studies for it, complete with official diploma.

Researchers from ETH Zürich, AO Research Institute Davos in Switzerland and INNOVENT in Germany, now have something new to introduce.

Essentially, they have created a material combination that can allow most 3D bioprinting processes to create cartilage ready for implantation.

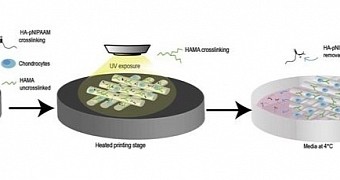

They combined pNIAAM, otherwise known as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), with hyaluronan (HA for short) to create an ink that stays in liquid form at room temperature but solidifies if printed onto a substrate heated at a human's normal body temperature.

They went further by adding a second polymer (hyaluronan methacrylate or chondroitin sulfate methacrylate, or CFMA) to render the scaffolds even more durable, thanks to crosslinking with the HA-pNIPAAM gel and forming a network.

Basically, the scientists used the original components of cartilage (chondroitin sulfate and HA, among others) and added a polymer that won't be rejected by the body but which will respond to heat and cause the whole mixture to harden.

Practical applications

Human trials won't start right away, but they may very well be less than one or two years away. Maybe less, given how many 3D printed replacement joints and other bones have been used already, even two skulls.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //