Countries that are working together to support the construction and operation of the International Space Station have decided on a new set of standards for docking systems, that would allow for greater flexibility in terms of docking in low-Earth orbit.

With the new guidelines in mind, space agencies that want to design new docking systems will be able to do so without having to create segments that are necessarily identical. Still, the systems in themselves will be compatible with each other.

The agreement materialized in the Interface Definition Document (IDD), which will be released to the general public on October 25. The International Docking System Standard (IDSS) will enter into effect soon, ISS participants say.

The main idea behind taking this approach to facilitating docking is versatility. While Russian and American spacecraft make their way to their respective ISS ports on their own (hard docking), other spacecrafts cannot do so.

This is the case of the new European ATV and Japanese HTV unmanned space capsules, which need to be captured using the Canadarm-2 robotic arm aboard the ISS, and docked with this mechanism.

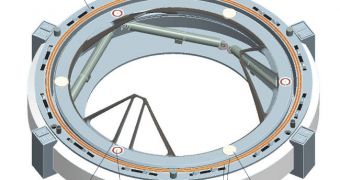

But the space partners decided that, regardless of the underlying platform, a compatible docking system is the way to go. Inspiration came from the Russian-built Androgynous Peripheral Attachment System (APAS), which allows for shuttle docking as well.

“The IDSS is an outstanding example of international collaboration. We have developed a common language for docking systems to use the same 'words' in space when it comes to work together,” explained at the meeting Simonetta Di Pippo.

“The Docking Standard sweeps away the boundaries for a truly global exploration endeavor. It will also make joint spacecraft docking operations more routine and eliminate critical obstacles to joint space exploration undertakings,” she added.

“Today (October 19), our future in space is more open-minded than ever. ESA has been committed to the development of this standard since the inception of the working group and has contributed to the document defining this standard interface,” di Pippo argued.

“We have been working for a number of years on the development of the IBDM (International Berthing Docking Mechanism) and we are willing to make the IBDM compatible with this new international docking standard,” she said.

Di Pippo is the director of the Human Spaceflight Division at the European Space Agency (ESA),

NASA, ESA, Roscosmos, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) are the main agencies involved in the ISS project.

They are also the members of the International Space Station Multilateral Coordination Board (MCB), the body that determines the faith of the entire endeavor.

One of the most important features of the new document is a detailed description of the physical features and design loads that a standard docking interface should have from now on.

MCB representatives say that, undoubtedly, additional refinements and revisions to the initial standards will be included in the document as the need arises.

“The goal was to identify the requirements to create a standard interface to enable two different spacecraft to dock in space during future missions and operations,” explains Bill Gerstenmaier.

The official is the MCB chair, and also the associate administrator of the Space Operations Mission Directorate at NASA's Headquarters, in Washington DC.

“This standard will ease the development process for emerging international cooperative space missions and enable the possibility of international crew rescue missions,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //