A new biomaterial, called hydrogel, can be injected into wounds where it starts repairing damaged tissue and regenerating it, opening the way for revolutionary treatments for injured soldiers. The gel also has surprising antibacterial properties which help speed up the healing process.

Hydrogels are made up of a network of polymer chains that do not dissolve in water, but can absorb large quantities of it, until water makes up over 99% of their mass. This water content makes them very similar to biological tissue and can be used to repair and heal various wounds, especially when human cells are added to their composition.

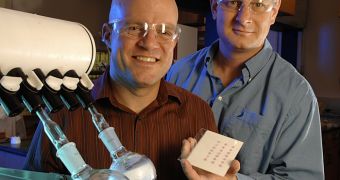

Joel Schneider, University of Delaware associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, together with Darrin Pochan, associate professor of materials science, invented the hydrogel that could be used in a variety of medical applications.

They hope that their product could one day be used to deliver cells into wounds, where they could start regenerating them and could even grow new bones and organs where the originals have been damaged by diseases.

The hydrogel is based on peptides, short molecules created by amino acids liked in a defined order and are the building blocks of proteins. This specific peptide, MAX8, a development of the original, MAX1 peptide can self-assemble in a particular shape in response to a stimulus, like light exposure and can be injected with living cells, before it is applied on the wound.

Once applied, it rapidly rigidifies and helps tissue regeneration while preventing bacterial infections. "They're like rebar when you're building something with concrete," Schneider said. "They give the cement something to hang onto."

"Although we have currently only demonstrated this capacity of our gels using simple models, we envision that when injected into the body, the cells encapsulated in the gel can go about their business in restructuring the tissue," Schneider explained.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //