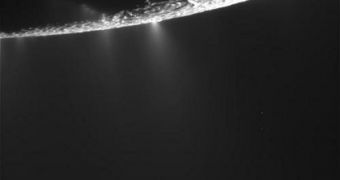

New data collected by the Cassini spacecraft has demonstrated once again that the possibility of a liquid ocean existing underneath the icy surface of Saturn's moon Enceladus is very significant. During its last fly-by of the celestial body, the NASA/ESA mission managed to discover clouds of negatively-charged water looming in the atmosphere above Enceladus, which may have only come from within the moon itself, during one of the instances in which it expels large amounts of water and ice vapors.

This type of water ions can be found on Earth as well, mostly around places where waterfalls exist, or where large bodies of water are in motion. “We see water molecules that have additional electrons added. There are two ways they could be added – from the ambient plasma environment, or it could be to do with friction as these water clusters come out of the jets, like rubbing a balloon and sticking it on the ceiling,” the BBC News University College London (UCL) Mullard Space Science Laboratory expert Andrew Coates reported.

A key discovery to support this idea is the fact that scientific instruments aboard Cassini have already discovered the specific signatures of salts inside the plumes, which are consistent with bodies of water that have been in contact with rocks near the core of the moon for a very long time. “While it's no surprise that there is water there, these short-lived ions are extra evidence for sub-surface water and where there's water, carbon and energy, some of the major ingredients for life are present. The surprise for us was to look at the mass of these ions. There were several peaks in the spectrum, and when we analyzed them we saw the effect of water molecules clustering together one after the other,” Coates adds.

The data on which these conclusions are based was collected by Cassini during a very close flyby of Enceladus conducted in 2008. The UK team published its findings in the current issue of the respected scientific journal Icarus. The measurements were collected with the Cassini plasma spectrometer (CAPS) instrument, which was originally designed to assess traits such as the density, flow velocity and temperature, in ions and electrons hitting it. This was supposed to paint a clear picture of the magnetic environment around Saturn, and no one thought that CAPS would eventually wind up analyzing the plumes of Enceladus.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //