50 years ago, a mining engineer discovered some fossils bones in a tunnel he was excavating looking for phosphate in Cebu island (Philippines), but the bones arrived to The Field Museum just after 40 years.

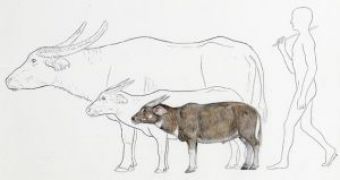

The bones proved to belong to a new dwarf extinct species of Asian water buffalo named Bubalus cebuensis. Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) stand six feet at the shoulder and reach 2,000 pounds (or even 3,000 pounds in wild forms) while B. cebuensis would have stood only 2.5 feet and reached 350 pounds.

B. cebuensis evolved from continental water buffalo and dwarfed living on a small island. This is the first well-supported example of "island dwarfing" among cattle. "Natural selection can produce dramatic body-size changes. On islands where there is limited food and a small population, large mammals often evolve to much smaller size," said Darin Croft, professor of anatomy at Case Western Reserve University.

Another close relative of the water buffalo and of the recently discovered species is the tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis), a highly endangered buffalo from Mindoro island (Philippines), itself a dwarf, although larger than the newly discovered species at about three feet tall and 500 pounds.

In the Sulawesi Island (Indonesia) there live another two dwarf buffalo species, but these are not so closely related to the water buffalo.

This discovery on Cebu, the presence of tamaraw on Mindoro and fossil buffalo teeth from Luzon point this genus might have once lived throughout the Philippines. The problem is that Philippines is an oceanic archipelago, never connected to continental land mass. "Documenting past mammal diversity in the Philippines, an area of extremely high conservation priority, is vital for understanding the evolutionary development of the modern Philippine flora and fauna and how to preserve it," said Larry Heaney, curator of mammals at The Field Museum.

"The concentration of unique mammal species there is among the very highest in the world, but so is the number of threatened species."

B. cebuensis can also help scientists to better understand "island dwarfing," whereby some large mammals confined to an island shrink in response to evolutionary factors. "Discovery of this new fossil water buffalo provides additional evidence that dwarf species can evolve quickly in isolation," said John Flynn, Frick Curator in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History.

"Other fossil dwarf mammal species likely remain to be discovered in the poorly explored island systems of tropical Southeast Asia."

The discovery of B. cebuensis supports the hypothesis that the tamaraw evolved to a small size due to its island habitat. The fact that B. cebuensis, living on a smaller island, dwarfed more than the tamaraw living on a larger island, supports the hypothesis that smaller islands produce smaller dwarfs. B cebuensis presents signs of mosaic evolution (dwarfing of the different parts were not correlated). For example, it had relatively large teeth, typical of island dwarfs, but also relatively large feet, unusual of dwarfing. "The reason that might be is because evolution actually works in different ways-we call it mosaic evolution-that not all features change in exactly the same way all the time. For whatever reason, this particular species didn't reduce the foot proportions the same way that dwarfs of other species on other islands might have," Flynn told.

The skeleton elements brought for study were two teeth, two vertebrae, two upper arm bones, a foot bone, and two hoof bones.

The scientists couldn't date precisely the fossil, but estimated an age of 10,000 to 100,000 years (it lived during the Pleistocene or "Ice Age") or even less.

Philippines hot and wet climate is not conducive to fossil preservation, but even so, fossils of elephants, rhinos, pig, and deer have been previously found. "We have wonderful living biodiversity, but we have known very little about our extinct species from long ago. Finding this new fossil species will spur us to new efforts to document the prehistory of our island nation." Dr. Angel Bautista, curator of anthropology at the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila.

This archipelago is formed by more than 7,000 islands, but during the peak of the last glaciation, 20,000 years ago, sea levels were about 400 feet lower and some of the islands were connected amongst them by land. Many mammals from mainland Asia, probably via Borneo island, migrated to the Philippines during this time by swimming short distances between islands. And water buffalo are good swimmers.

At the end of the glaciation, when the glaciers melted, sea levels rose, and those mammals got trapped on their islands. Later, they evolved in the unique dwarf species.

Another current Philippines dwarfs are Calamian deer (Axis calamianensis) from Calamian Islands or Visayan spotted deer (Cervus alfredi) from Visayan Islands.

About 200 native mammal species currently live in the Philippines, and nearly 60 % of them are endemic. This endemics percentage is surpassed only by Madagascar.

Image credit: Velizar Simeonovski/The Field Museum Bubalus cebuensis' size compared to tamaraw, water buffalo and man

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //