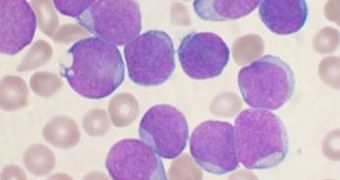

Investigators at the University of Cambridge, in the United Kingdom, announce the creation of a new drug that can be used to treat one of the most common forms of blood cancer, mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL). The condition oftentimes affects babies.

In a paper the team published in the October 2 issue of the top scientific journal Nature, the group says that the drug showed great promise in trials, and that they plan to extend their tests even further.

In excess of 10 percent of all adults diagnosed with leukemia have MLL. The situation is however more severe in children, where 80 percent of all acute leukemia cases are believed to be accounted for by MLL. Standard treatments oftentimes fail for these people.

Even if they succeed, the disease has the nasty habit of coming back later. This happens because this form of blood cancer also has a genetic foundation. In patients, the MLL gene is fused with another, neighboring gene, a phenomenon that creates a harmful fusion protein.

The molecule then goes on to switch on a series of genes that have been linked to the development of leukemia. There are very few things oncologists can do to prevent the protein from misbehaving.

The new investigation included experts from the Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute and the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research. Researchers from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Cellzome AG also contributed to the research, which was financed by Cancer Research UK.

Together, investigators determined that BET family proteins are responsible for leading the fusion proteins to their targets, the genes responsible for causing leukemia. The BET molecules recognize certain chemical tags in the scaffolding holding DNA, called chromatin, and homes in on them.

The GSK-developed chemical compound I-BET151 has proven capable of diverting the attention of BET proteins, therefore preventing them from delivering the fusion proteins to their initial targets.

Experts with the research group say that this method has thus far been used exclusively on mouse models and in human cancer cell cultures in the lab. However, the approach proved to work, so the team is hoping to move forward with clinical trials soon.

“Our work shows that this type of leukemia is reliant on MLL being able to bind to chromatin via BET proteins,” explains the deputy director of the Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute, professor Tony Kouzarides. He is also the co-leader of the investigation.

“This 'epigenetic' approach to therapy – which targets chromatin rather than DNA – is an exciting new avenue for drug discovery which we hope will be useful for other types of cancer in addition to MLL-leukemias.” he goes on to say.

“MLL leukaemia is very hard to treat and often the only option for patients who have become resistant to standard treatments is a bone marrow transplant. We hope these findings may in future mean that fewer children need this procedure.” Dr. Brian Huntly adds.

He holds an appointment with the University of Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, and was also a co-leader of the new study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //