International maritime laws currently forbid disposal of plastic materials at sea.

Plastics are very tricky for the marine environment.

They break down extremely slowly and the resulting products are very toxic. Moreover, some plastic can fool some species (like marine turtles) to be taken as jellyfish and many individuals from already endangered species die from suffocation with plastics.

Now, a biodegradable plastic that breaks down into nontoxic components in seawater could make it environmentally safe to get rid of "disposable" forks, spoons, wraps and other waste plastics overboard from often crowded ships. "There are many groups working on biodegradable plastics, but we're one of a few working on plastics that degrade in seawater," said researcher Robson Storey, a polymer scientist at University of Southern Mississippi. "We're moving toward making plastics more sustainable, especially those that are used at sea."

Cruise liners, naval warships and other vessels produce huge amounts of plastic trash, like stretch wrap for large cargo objects, food containers and plastic table ware. This garbage often remains on board for long periods of time until ships reach a port.

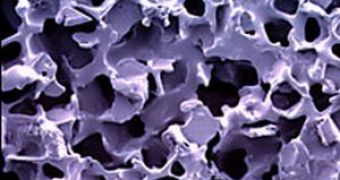

The new plastics, when exposed to seawater, can break down in as few as 20 days and are made of polyurethane designed to incorporate a biodegradable chemical (PLGA) employed in medical sutures.

The new material can be from soft and rubbery to hard and rigid, being potentially useful for many applications. "Our goal is for them to break down into carbon dioxide and water," said Storey.

Among other byproducts of the degradation of this plastic there's the lactic acid, abundant in milk, but found in fact in all organisms, especially in the muscle, as it is also a byproduct of glucose burning in organisms (we get muscular fever when there's too much lactic acid in our muscle cells due to an intense effort).

"The new plastics are denser than saltwater, making them inclined to sink rather than float. This could help prevent them from washing up on shores and polluting coastlines. The plastic is undergoing degradation testing at military and university labs, and initial results are promising," Storey said.

The product has not been checked in freshwater. Future investigation will improve the plastics for changes in temperature, humidity, seawater composition and other environmental factors.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //