A new alloy created in the United States can be controlled via magnetism, opening the way for new applications in sensor and micromechanical device applications. The multi-institution research group that carried out the work was coordinated by experts at the University of Maryland (UMD).

The alloy was obtained by combining a centuries-old metallurgy technique with the latest research in material science. In addition to relying on commonly-available chemicals such as cobalt and iron, the material is also capable of doing without rare-Earth elements.

REE represents a class of compounds that are required for building most of today's electronics and high-tech equipment, ranging for transistors and microprocessors to spacecraft, solar panels, wind turbines, headphones and everything in between.

As their name suggests, they chemicals are not easy to come by, so investigators have been looking for a way of replacing them for quite some time now. The new alloy might just be the break researchers need in this regard.

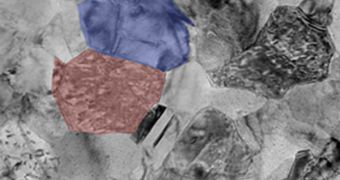

The structures and mechanical properties of the new material were carefully determined by a group of scientists based at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The team was part of the larger collaboration that recently announced the alloy.

One of the most interesting aspects of the new material is the fact that it displays a property called giant magnetostriction. What this means is that applying a sufficiently-strong magnetic field to the material will lead to significant changes in dimension.

Physicists say that the approach is similar to the piezoelectric effect, which occurs when members of certain classes of ceramics and crystals are mechanically deformed. The change in shape leads to the production of a small electrical current, which can then be harvested.

The cobalt-iron alloy could be used to create highly-sensitive magnetic field detectors, in addition to small devices called actuators, to be employed in micromechanical instruments. What is remarkable about the material is that it does not need any electrical wires, unlike piezoelectrics.

“Magnetorestriction devices are less developed than piezoelectrics, but they're becoming more interesting because the scale at which you can operate is smaller,” NIST materials scientist Will Osborn explains.

“Piezoelectrics are usually oxides, brittle and often lead-based, all of which is hard on manufacturing processes. These alloys are metal and much more compatible with the current generation of integrated device manufacturing. They're a good next-generation material for microelectromechanical machines,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //