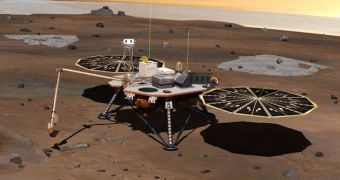

The Phoenix lander mission to the Red Planet arrived in the northern regions of Mars in 2008, and immediately started conducting its studies, which were aimed at discovering water-ice beneath the surface. It didn't take long for it to discover the stuff, as, during landing, its “feet” dug into ice on their own. With the certainty that ice exists in those regions, NASA is currently planning a new generation of landers and rovers that could be used to drill through the layer of water-ice, in search for signs of life.

Though the area appears to be deserted now, and is nothing more than a freezing wasteland, things weren't always that way. In the not-so-distant past, Mars' tilt was different than it is today, and the regions that are now at the north pole received sufficient amounts of heat to allow for the formation of liquid water. According to experts, the amounts of water were significant enough to, at least in theory, allow for primordial life to appear. The goal of a future robotic drill on the Red Planet would be to search for signs of primitive bacteria and other microorganisms, Space reports.

In order to prepare for this endeavor, NASA is scheduled to begin its IceBite project this week, at a secluded location known as the University Valley. The area is a part of the larger McMurdo Dry Valleys, in Antarctica. Perched some 1,600 feet above sea level, the valley provides the team with ice sheets that are very similar in numerous traits to its counterparts on Mars. Therefore, it constitutes one of the few suitable places for this type of project in the world. Being able to drill in thick ice would be very important for a future robotic mission to Mars. Therefore, practice is crucial for optimizing the mission parameters.

“Everywhere in the northern hemisphere where there's permafrost, it is wet and it gets muddy in the summer. There is always a point in the summer where you have wet soil and then ice and so the temperature at that boundary is zero degrees [Celsius],” the IceBite principal investigator, NASA Ames Research Center expert Chris McKay, explains. “In Antarctica, and only in Antarctica, we find a completely different phenomenon called dry permafrost. The whole system never gets warm enough for that ice to turn to liquid. That's the relevant model for Mars.”

“We'll look at the physics of the soil, the water moisture. We'll look at the snow packs that are surrounding the valley. And we'll stick in all sorts of data loggers and temperature and environmental loggers to record what's going on,” McKay concludes. The IceBite project is funded by the NASA ASTEP (Astrobiology Science and Technology for Exploring Planets) program, for a period of three years.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //