Unbelievable as it may seem, one of the most closest planets to Earth may pose some of the deepest mysteries about the solar system. Mercury, the smallest of all the planets in the solar system, having the closest orbit to the Sun, is the least studied of all. More than half of the planet's surface is not yet catalogued, virtually nothing is known about its magnetic field and its inner structure, what lies between the planet and the Sun, or why it is so dense and mostly made of heavy elements.

During the whole duration of the solar system exploration program which involved studying the planets, only one probe has been sent towards Mercury, Mariner 10 that was launched in 1973 and made a total of three flybys around the small planet, before running out of fuel two years later. NASA's MESSENGER probe, the second ever probe sent to Mercury, was supposed to make its first flyby around the planet today, before entering a long orbit around it.

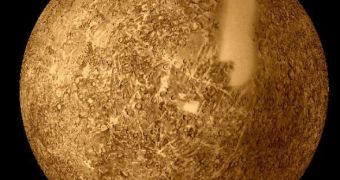

During its mission, Mariner 10 was only capable of mapping about 45 percent of the surface of Mercury, revealing a landscape littered with craters, meaning that more than half of its surface is virtually unknown, and safe from keen eyes trying to study it from the surface of the Earth. Mariner 10 revealed that the planet experiences temperatures as high as 425 degrees Celsius of the sunny side, and even at those temperatures astrophysicists believe that the planet may have ice on its surface, hidden in deep craters away from the action of the Sun. During its survey, MESSENGER will be constantly monitoring its poles, in the hope that it might detect traces of hydrogen that could then be associated with the existence of water on its surface.

Planet formation theory argues that the planet might go through a shrinking process, as its inner core cools over time. Mercury is too little to present plate tectonics; however, Mariner 10 revealed that the surface crust of the planet buckled and formed large cliffs, some more than a mile high and a few hundreds miles long.

What lies between the Sun and Mercury? Beats me, albeit astronomers believe that an inner ring of small asteroids may be hidden by the contrast ratio of the Sun and the respective asteroids. MESSENGER may detect such features, as it closes near to the planet.

Not only that Mercury has an atmosphere, but it is incredibly unstable, say the astronomers. Gas is being lost routinely due to the action of the solar wind. Nevertheless, it should have lost the whole quantity of gas in the 4.6 billions of years since the planet first formed. Why does it still have gas, and how does it replenishes its quantity?

The simpler, the better... gas is being constantly pushed towards Mercury from the Sun, creating a hydrogen and helium rich atmosphere, which are then carried out towards the outer regions of the solar system by solar wind. A second theory argues that gases are being evaporated from Mercury's surface or they are brought by comets and asteroids.

Why is the core of the planet still molten? Such a small planet should have cooled long ago, even though it is the closest to the Sun. Its weak magnetic field cannot be explained by its small spin speed. Originally, astrophysicists believed that such a small spin speed would not be enough to generate a detectable magnetic field, thus it must be a remnant from the past. But Mercury's core is still molten, thus the magnetic field can only be explained though the fact that it is being actively generated in much the same way our planet generates its magnetic field.

Its bizarre high density represents another odd feature of the planet. Scientists currently believe that about two thirds of the planet's mass might be represented by its iron core. Theories trying to explain this weird particularity involve the fact that the original surface of Mercury might have been ejected during large collisions with asteroids, which might have also pushed it into its current orbit. Nevertheless, the shifted orbit theory seems a little too odd, and most of the scientific community believes that the planets mostly remain in the places where they have formed.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //