The latest dataset produced by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Planck Telescope reveals the existence of a mysterious haze made up of microwaves throughout the Milky Way. The observatory also found several previously unknown islands of very cold hydrogen gas in the galaxy.

According to astronomers studying the datasets, the main reason why Planck was launched was to help scientists make more sense of the blueprint underlying the entire structure of the Universe. Full details of the analysis will be presented at an international conference in Bologna, Italy, later this week.

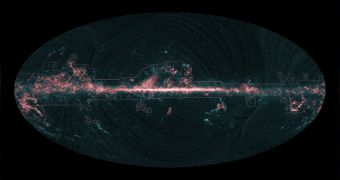

One of the most useful scientific tools Planck produced is an all-sky map of carbon monoxide concentration and distribution in the galaxy. The gas is one of the main components of galactic gas clouds, right alongside hydrogen.

Though hydrogen far surpasses CO in quantities, the development of new stars from these gas clouds would be nearly impossible without the latter. As such, knowing its distribution is essential for predicting the rate at which new and old galaxies alike will produce new stars.

Additionally, CO gives off a lot more light than hydrogen does, which means that the carbon compound can be used as a proxy for discovering the largest H2 clouds in the galaxy. “Planck turns out to be an excellent detector of carbon monoxide across the entire sky,” says Dr. Jonathan Aumont.

The expert, a collaborator with the Planck team, is based at the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Universite Paris XI, Orsay, France. “The great advantage of Planck is that it scans the whole sky, allowing us to detect concentrations of molecular gas where we didn’t expect to find them,” he adds.

But the most intriguing discovery the telescope made has to be the seemingly-ubiquitous haze of microwave radiations that appear to permeate the Milky Way. There is currently no explanation for why this haze exists, or what caused it.

Planck did manage to identify the area immediately adjacent to the galactic core as being the most probable source for these emissions. Some astrophysicists say that the radiations appear to be a form of a type of energy called synchrotron emissions.

The latter are usually produced when electrons previously accelerated to relativistic speed during supernova explosions pass through intense magnetic fields. Such fields can be found around black holes – including the Milky Way's Sagittarius A* – but also around all types of neutron stars.

An interesting aspect of the microwave haze is that it displays significantly different properties from the synchrotron emissions astrophysicists identified as originating elsewhere in the galaxy.

Some of the explanations already set forth to explain the phenomenon include increased supernova explosion rates near the galactic core, the action of intense galactic winds, or even the annihilation of massive dark matter particles. However, none of these hypotheses has been tested thus far.

“The results achieved thus far by Planck on the galactic haze and on the carbon monoxide distribution provide us with a fresh view on some interesting processes taking place in our Galaxy,” ESA Planck project scientist Jan Tauber explains.

“We look forward to characterizing all foregrounds and then being able to reveal the CMB [cosmic microwave background] in unprecedented detail,” he adds. The expert concludes by saying that the first cosmological dataset is expected to be released by the Planck Collaboration next year.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //