A new study revealed that only the relatively low current oxygen level impedes insects to gain huge proportions. "The study adds support to the theory that some insects were much larger during the late Paleozoic period because they had a much richer oxygen supply," said Alexander Kaiser, insect physiologist at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona.

During the Paleozoic era - about 300 million years ago - giant insects roamed the Earth like dragonflies with a hawk wingspan ( at 2.5 feet or 80 cm) (image center). "The air's oxygen content was 35% during this period, compared to the 21% we breathe now", Kaiser said.

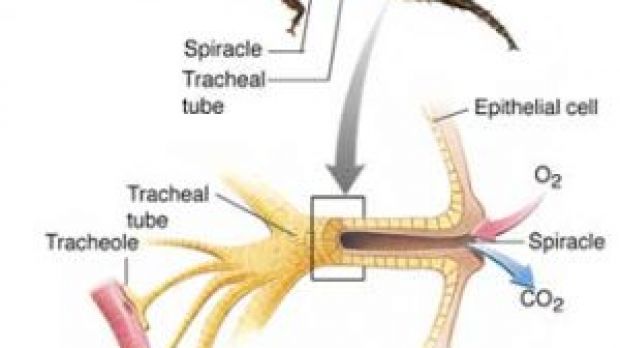

The higher oxygen concentration is suspected to stay behind the huge size of those insects. Not all the Paleozoic insects were giants, but still, "maybe 10 % were big enough to be considered giant," said Kaiser. The background for these occurrences is physiological and anatomical: insects don't use blood to transport oxygen to the tissues. Air enters and gets out of their body through many paired holes called spiracles. "These holes connect to branching and interconnecting tubes, called tracheae," Kaiser explained.

While terrestrial vertebrates have one trachea, insects have a ramified tracheal system that transports oxygen directly to the tissues and removes carbon dioxide.

With the growth, tracheal tubes get longer to reach peripheral tissue, and get broader or multiply due to the additional oxygen demands of a larger body. Closing their spiracles, the insects limit the oxygen intake and live off the oxygen they already have in their tracheae, making them very hardy to drowning or air pollution.

The researchers explored the link between insects' size, tracheal system and the oxygen amount in the air. The researchers used x-ray images to compare the tracheal dimensions of four species of beetles, ranging in size from 3mm (Tribolium castaneum, about one-tenth of an inch) to about 3.5 cm (Eleodes obscura, about 1.5 inches). Beetles ( Order Coleoptera) are evolved insects and appeared after the Paleozoic period, but Kaiser's team used these insects because they are much easier to keep in the laboratory than dragonflies.

Through X rays "The study found that the tracheae of the larger beetles take up a greater proportion of their bodies, about 20% more, than the increase in their body size would predict," Kaiser said.

This is because the tracheal system is not only becoming longer to reach longer limbs, but the tubes increase in diameter or number to take in more air to handle the additional oxygen demands. The disproportionate increase in tracheal size reached a critical point at the joint between the leg and body.

"When tracheal size is limited, so is oxygen supply and so is growth," Kaiser explained. Using their results, the study team calculated that beetles could not grow larger than about 15 centimeters. "And this is the size of the largest beetle known: the Titanic longhorn beetle, Titanus giganteus (photo bellow), from South America, which grows 15-17 cm," Kaiser said.

This puzzles the next issue: why the Paleozoic insects were not limited in their growth by these critical limits? In fact, the Paleozoic insects had the same anatomy, including their tracheal system, but were just bigger. The explanation resides in the oxygen concentration in the atmosphere during that time. The insect needed smaller quantities of air to meet their oxygen demands. "The tracheal diameter can be narrower and still deliver enough oxygen for a much larger insect," Kaiser concluded.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //