Mont Saint Michel is a rock located on the English Channel, in the gulf between the peninsulas Bretagne and Cotentine, at just 2 km off the French coast, to which it belongs.

It had only 50 m (150 feet) in height and slightly over 100 m (300 feet) in diameter.

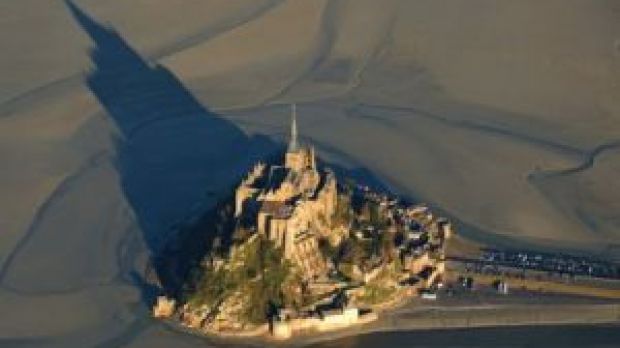

It is the most visited place in France after the Eiffel tower for two reasons. First, here occurs one of the most spectacular tidal phenomena in the world: during the low tide, Mont Saint Michel is a peninsula (photo above), being bound to the continental mass through a sand spit, while during the high tide it is an island (photo below). In this area, one of the most powerful tides on Earth manifests, twice a day, with a 13-15 m (39-45 feet) difference between low tide and high tide.

Once the tide was even bigger, of 50 m, as it happened in 709, when the trees covering Mont Saint Michel were swept away, leaving a desolate rock. An engraving from the 8th century reveals that the binding zone to the continental mass was forested, thus the rock was a peninsula.

Till the beginning of the 8th century, the rock was called Mont Tombe ("Tomb Mountain"), as it looks like a tomb amidst the smooth large areas of sand.

The second attraction of the island is its architectonic ensemble, a medieval fortress, built in romantic and gothic styles during the 11-13th centuries. The fortress resisted many wars and fires and was never conquered.

During the 100 years war, between England and France, when most of France was occupied by the English troops, this was the only place in Normandy that never surrendered to the enemy, resisting in 1434 the siege of an English army of 20,000 troops, a fabulous number for those times.

On the island, a monument dedicated to the Saint Michael ("Saint Michel" in French) was located. In the year 1000 a small church was built over the monument. In 1058, a romantic monastery was inaugurated on the island. A gothic monastery would be built between 1203-1228, with external walls 40 m (120 feet) tall.

The rest of the rock is occupied by a small village, which is gone through by a sole spiraled street.

Today, the island is on peril of becoming a permanent peninsula, as the dam-roadway made 100 years ago to connect it to the mainland impedes the water circulation between the rock and the continent, water that sweeps the sediments. Soon, the sediments around the rock could be 2-3 m (6-9 feet) thick and then only one tide from ten will cut off the rock from the mainland. One solution to this would be the replacement of the last 450-600 m (1,350-1,800 feet) of the dam by a bridge.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //