Investigations conducted by the NASA Cassini spacecraft late last year allowed experts to discover that the deserts on Titan, the largest moon orbiting Saturn, were not as arid as first thought. Planetary scientists say it's no doubt the space probe readings indicate the presence of methane rain above them.

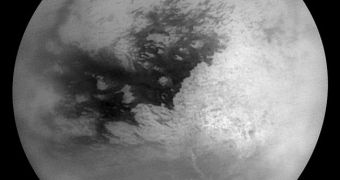

At first, Cassini photographed a large patch of ground near the equatorial areas of the moon. Its instruments monitored the area as it was getting darker and darker, before growing lighter in subsequent weeks.

At this point, experts had already become interested in the phenomenon. They did not know what was happening on Titan, but they knew they were on a brink of a significant finding. Eventually, they figured out the mystery of the darkened region.

Previous studies had indicated that the area over which the structure developed was covered by nothing more than vast and arid dunes, forming a desert, for all intents and purposes, Space reports.

But Cassini readings taken on and around September 27, 2010, showed that the formation was in fact a thunderstorm, which rained liquid methane above the area once thought to be a desert. This type of hydrocarbon is very common on Titan.

Due to the low average temperatures on the moon (around -190 degrees Celsius), water is frozen in blocks tougher than granite. However, methane and ethane become liquid at this temperature.

They have entered the moon's atmospheric cycle, and thunderstorms produced on Titan rain down these two chemicals, rather than water. Massive lakes at the two poles contain vast amounts of both hydrocarbons. The North Pole appears to have the most lakes.

The main implication of the new Cassini findings is that the Saturnine moon appears to have a rainy season. The prove analyzed a surface area some 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) long and 62 miles (100 km) wide.

“The poles are the only places that we have seen liquid in the form of lakes and seas, and we've seen cloud activity at the South Pole, but what was really exciting was to see this activity at the equatorial latitudes that are predominantly arid,” says Elizabeth Turtle.

The expert, a research scientist at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), believes that these manifestations are a clear indicator that Titan had a wetter climate several hundred thousands of years ago.

Turtle is also the lead author of a new research paper detailing the findings. The work appears in the March 18 issue of the top journal Science.

“It was expected that there might be seasonal changes in the weather pattern, but we didn't know for sure whether the rain had occurred in the past to carve the channels or if it's actually occurring right now,” Turtle explains.

“What these observations indicate is that it's occurring seasonally, and now is the season when it rains at the equator,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //