A group of investigators at the University of British Columbia (UBC) announces the discovery of a molecular pathway that is involved in the internal guidance system that allows immune cells to find and identify pathogen fragments.

This mechanism is therefore absolutely essential to our body's defenses. When the ability to detect foreign invaders is lost, then viruses, fungi and bacteria can easily gain a foothold inside humans, eventually killing them.

When pathogens invade, some fragments accidentally run into immune system cells. This is the latter's chance to identify the foreign bodies, and alert other cells of their presence. But, if the moment passes, then the infection can gain a foothold more easily.

Details of how the team conducted its investigation were published in last week's issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nature Immunology. The pathway the team discovered is controlled by a molecule called CD74. Using it may help doctors develop vaccines for cancers and viral infections.

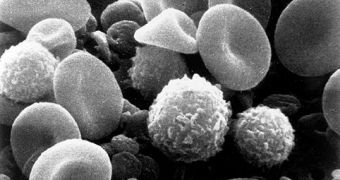

Researchers discovered the molecules inside dendritic cells, a population of cells controlling the primary immune responses of mammals. CD74 is apparently an important component in the cells' molecular machinery.

Dendritic cells rely on the Major Histocompatability Class I (MHC I) cellular receptor to detect and impact pathogen fragments. What gave MHC 1 the ability to do so has remained a mystery until now.

“This could ultimately lead to a blueprint for improving the performance of a variety of vaccines, including those against HIV, tuberculosis and malaria,” says team leader Wilfred Jefferies, who is a biologist at UBC.

“This detailed understanding of the role of CD74 may also begin to explain differences in immune responses between individuals that could impact personalized medical options in the future,” the researcher goes on to say.

He adds that CD74 play an important role in binding some of the MHC 1 receptors with pathogen fragments contained within the immune cell. When this happens, the receptors find it easier to identify invaders, and then go on to alert T immune fighter cells.

The latter then start dividing, and go after the pathogens with everything they've got. Usually, this means that the virus or bacteria is destroyed. In HIV infections, for example, this response is shut down, preventing the body from responding for what is happening to it.

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

The Nature Immunology study is available here.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //