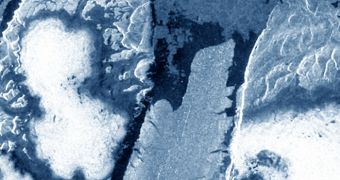

The large iceberg that broke off the Petermann Glacier in Greenland about a month ago is now making its way into the Nares Strait, satellites observations reveal.

The massive piece of ice broke away from the glacier in August 5, and has been slowly moving away ever since. It represents about one quarter of the former surface the glacier had.

The Nares Strait is a small body of water that connects the Lincoln Sea and the Arctic Ocean with the Baffin Bay. It can easily become clogged with a piece of ice the size of the new iceberg.

Scientists are very worried about the fact that the calving took place, given that Petermann is one of only two glaciers left in Greenland that still end in a floating shelf.

Satellite data reveal that the ice block currently floating in the Strait is about four times the size of the island of Manhattan, and that it represents 25 percent of the 43 mile (70 kilometer) floating shelf the glacier had.

Researchers at the University of Delaware say that this is the largest iceberg to calve from Greenland in the past five decades, which is saying a lot.

“The newly born ice-island may become land-fast, block the channel, or it may break into smaller pieces as it is propelled south by the prevailing ocean currents,” explains expert Andreas Muenchow.

“From there, it will likely follow along the coasts of Baffin Island and Labrador, to reach the Atlantic within the next two years,” adds the expert, who is also an associate professor of physical ocean science and engineering at the University of Delaware.

The iceberg could soon make its way into the Strait entirely, but precisely when this happens is entirely dependent on prevailing winds, and on ice blocks that may exist in the ice block's path.

Since it broke away from the glacier, the iceberg traveled about 22 kilometers, or 14 miles, until August 22. By September 1, it had moved another 4 miles (6 kilometers) towards the Strait.

Over the past few years, more and more glaciers around the world began shedding icebergs at increasing rates than ever before.

Researchers attribute this type of behavior to the growing influence of climate change and global warming, and to the fact that oceanic waters appear to be experiencing higher temperatures.

The waters then heat up the glaciers from underneath, thinning them, and setting the stage for massive calving. However, those of the current magnitude are rather rare, OurAmazingPlanet reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //