For years, astronomers and geologists have been debating whether a surface ocean made of liquid water actually existed on the surface of Mars. The latest research on the issue demonstrates that was the case.

The argument has swung back and forth countless time, with each new investigation offering arguments for or against the topic being discussed. What became apparent over the past few years is that Mars was a wet planet in its earlier days.

Rovers such as Spirit and Opportunity, landers such as Phoenix, and several orbiter discovered signs of groundwater, lakes, water canals, rivers, hot springs and deltas on the surface of the Red Planet, and all hinted towards the existence of a liquid ocean in the northern hemisphere as well.

However, conclusive proofs to tip the balance one way or the other have been lacking. The new study, published in the January 19 issue of the esteemed journal Geophysical Research Letters, contains data collected from the European Space Agency's (ESA) Mars Express orbiter.

The Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) low-frequency, pulse-limited, ground-penetrating radar aboard the Mars Express was responsible for collecting the data that informed the new investigation.

The investigation was led by University of California scientist Jérémie Mouginot, who believes that the Oceanus Borealis was real. This is the name that proponents of the landscape feature gave to the hypothesized Martian ocean, Universe Today reports.

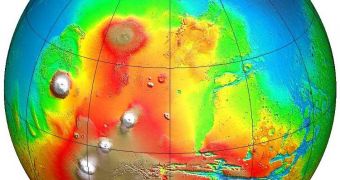

At this time, the region is called the Vastitas Borealis Formation, and MARSIS mapped all of its sedimentary deposits from orbit. A layer of volcanic deposits is located about 100 meters (328 feet) below layers of sediments that may have been deposited by an ocean.

““Although much is still unknown about the evolution and environmental context of a Late Hesperian ocean, our observations provide persuasive evidence of its existence,” the research team explains.

“The measurement of a dielectric constant of the Vastitas Borealis Formation […] is sufficiently low that it can only be explained by the widespread deposition of (now desiccated) aqueous sediments or sediments mixed with massive ice,” the researchers add.

“As such, the formation represents the best geologic evidence to date for the existence of an ocean in the Late Hesperian, about 3 billion years ago,” the research paper concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //