Mission planners currently designing there-and-back missions to Mars are faced with a very serious issue that has nothing to do with the impact of long-term isolation on astronauts, or with how to power up a spacecraft able to reach the Red Planet. In short, they are trying to determine how to suppress ATP molecules, which are the main source of energy for living things. The molecule, adenosine triphosphate, which is able to store large amounts of energy, can survive for months, or even years, on space probes, so a future expedition would run the risk of announcing that they've found life on Mars, when in fact they're holding readings of Earth-based organisms.

University of Florida expert Andrew Schuerger led a team of experts in conducting a simulation of how ATP would degrade in the Martian atmosphere. The conclusions were not at all good, the group announced. In addition, they said, ATP molecules had undoubtedly found their way on every rocket, shuttle, probe, lander, orbiter or rover that had ever blasted-off from our planet to miscellaneous destinations in the solar system and beyond. “It turned out that under normal equatorial Mars conditions the ATP was a lot more stable than we anticipated,” Schuerger shared, quoted by LiveScience.

At this point, the best bet that national space agencies have at finding life, or at least traces of past life, on Mars is to dig deep in the soil and analyze samples recovered from various depths. But such readings could easily be tainted by ATP molecules residing on the instruments themselves. Under these circumstances, missions such as NASA' Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) and ESA's ExoMars could be compromised even before they leave the planet, as doubts would always hang over any of their findings.

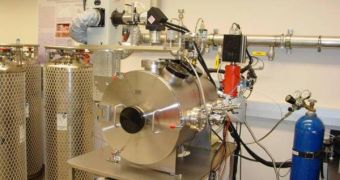

Schuerger and his team argued that the only way to save these missions from contamination would be to strengthen pre-launch cleaning and decontamination protocols. Still, they said that these measures might not suffice in removing all the stowaway ATP molecules hitching a ride to wherever the rocket was blasting off. The UF team conducted its research using the Martian Simulation Chamber (MSC), a cylinder in Schuerger's lab, where conditions ranging from radiation and ultraviolet levels to wind and temperatures were set to match those found on the Red Planet.

They learned that DNA, for example, disappeared within a few Martian days (or sols) from Sun-exposed surfaces, on account of the ultraviolet radiation that easily passed through the planet's ozone-less atmosphere. Under these circumstances, the surface of a spacecraft would be sterilized in the first sol of its arrival. But ATP endured for 158 sols directly exposed to the Sun, and for 32,000 sols, or roughly 50 Martian years, in the shades.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //